Credits

This exhibition was curated by Paul Barnaby, with assistance from Elizabeth Lawrence and Bianca Packham.

The cover photograph is by Mark Ferguson Photography.

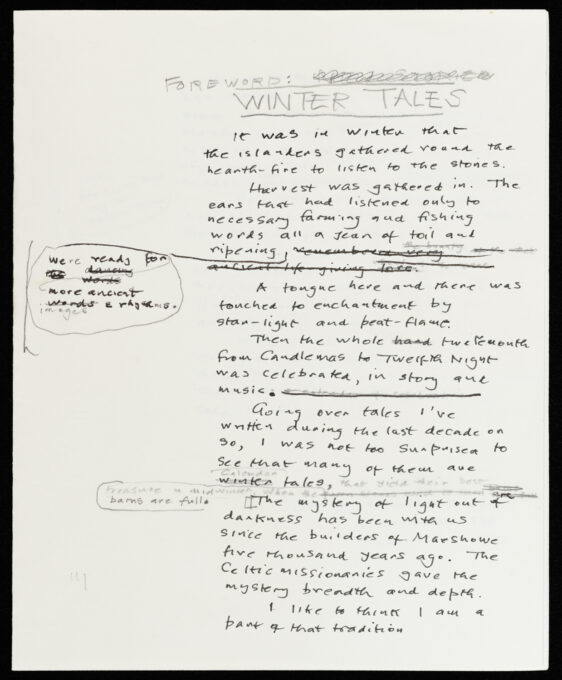

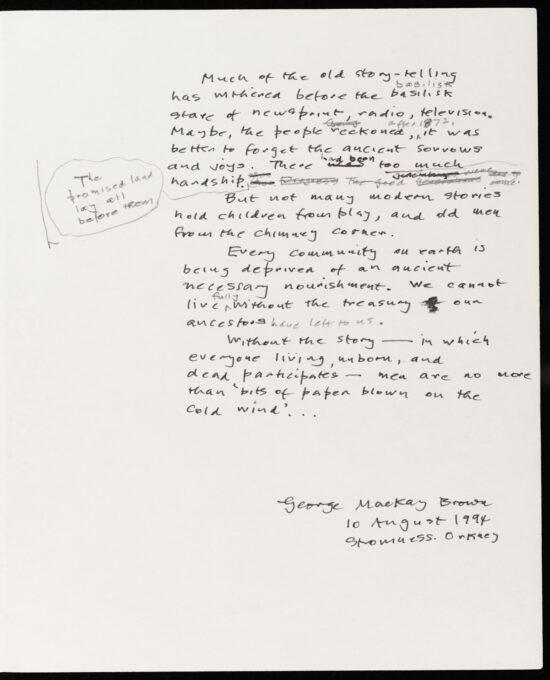

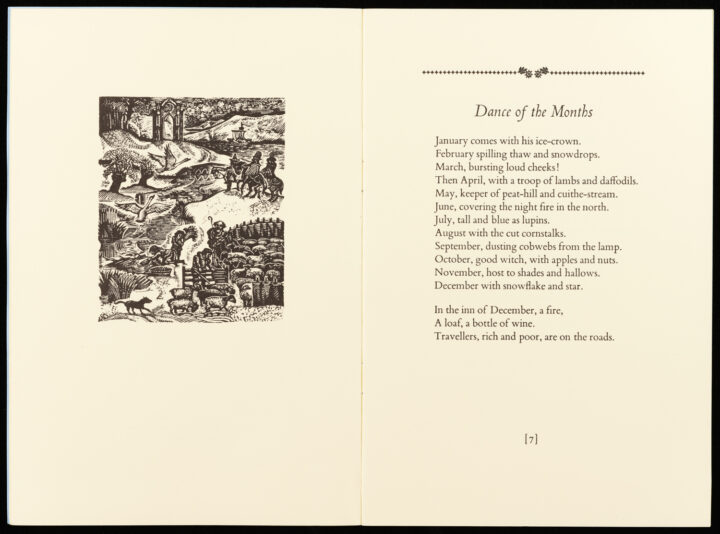

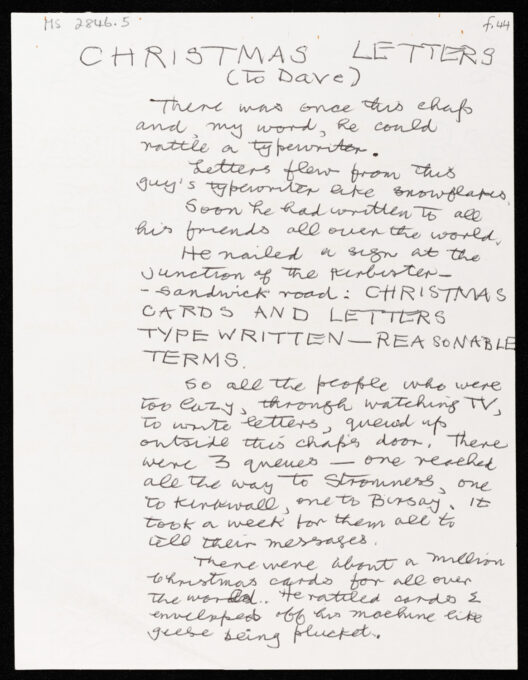

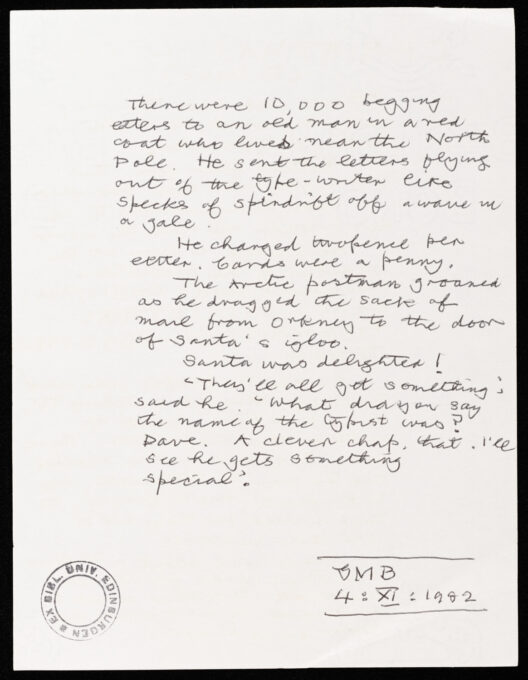

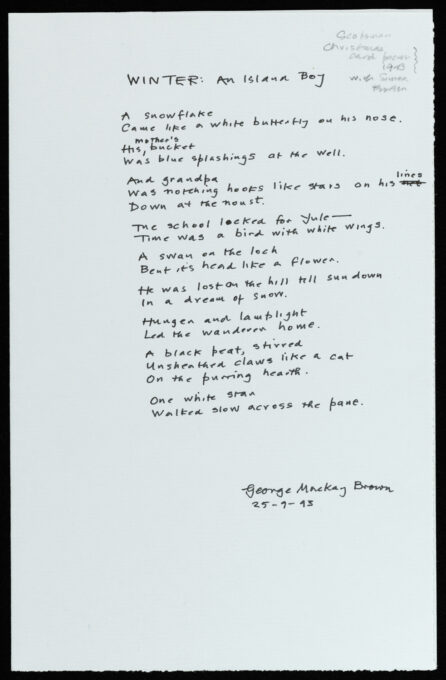

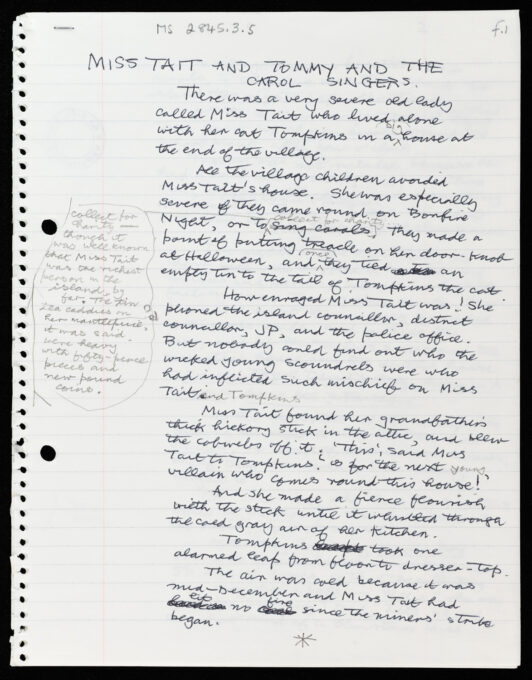

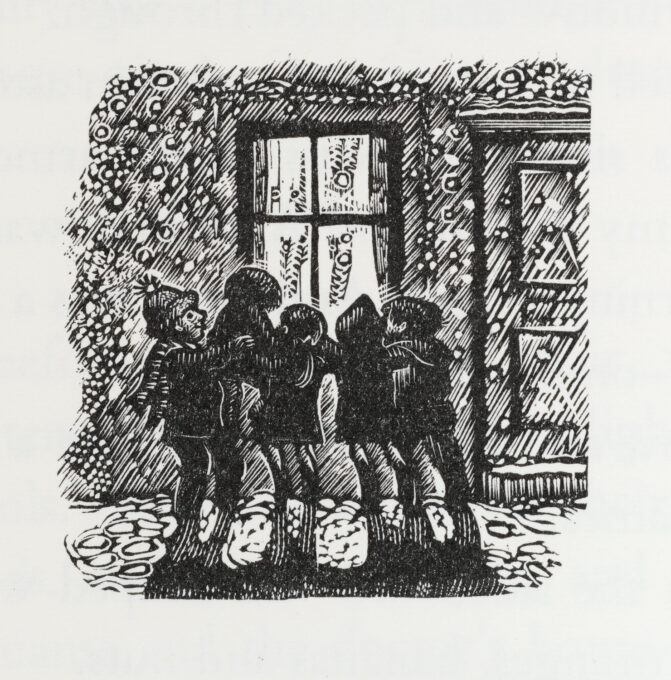

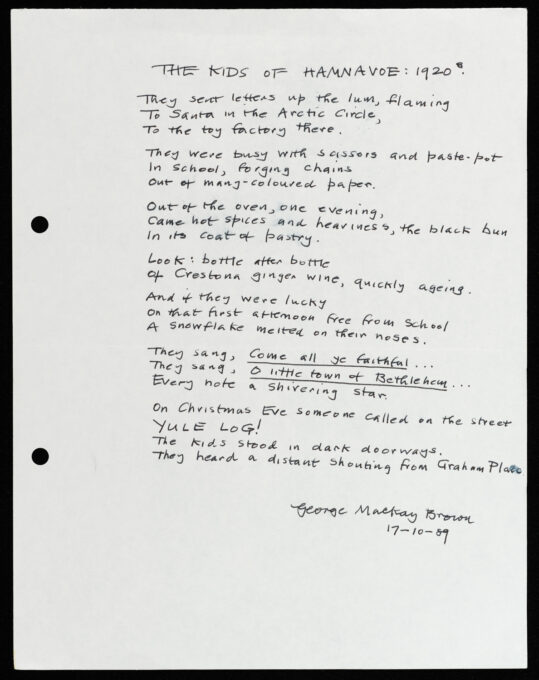

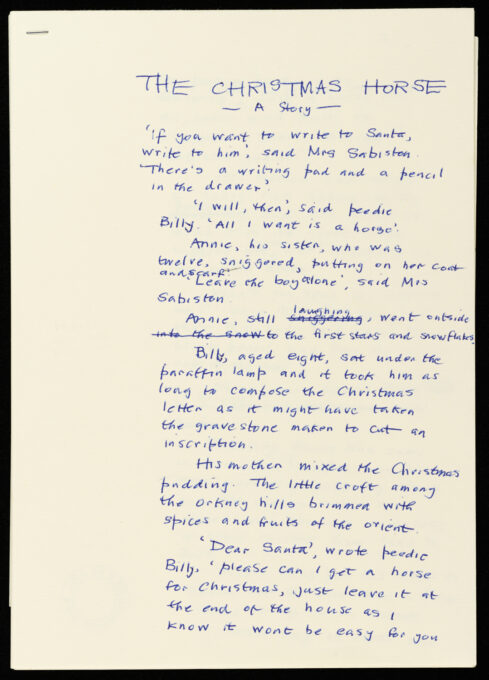

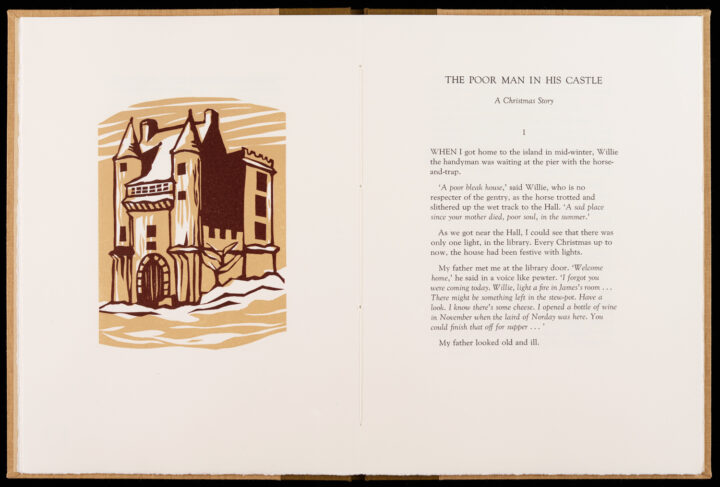

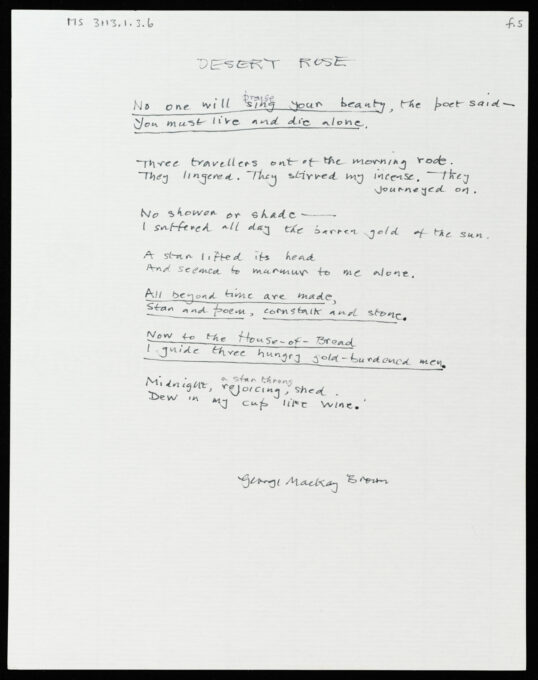

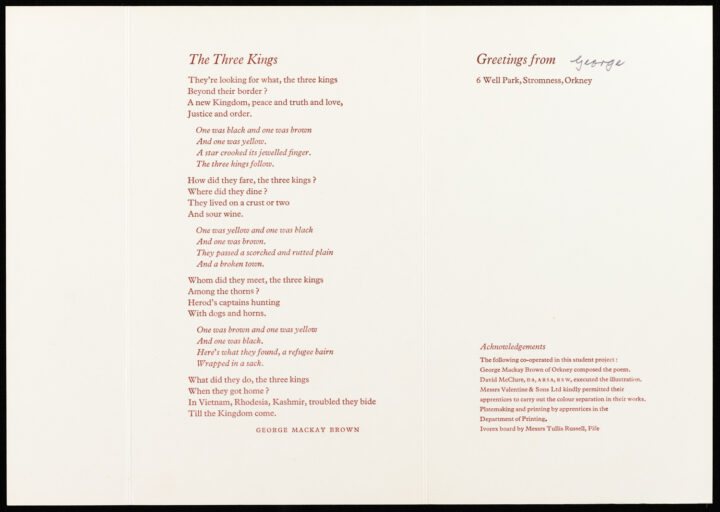

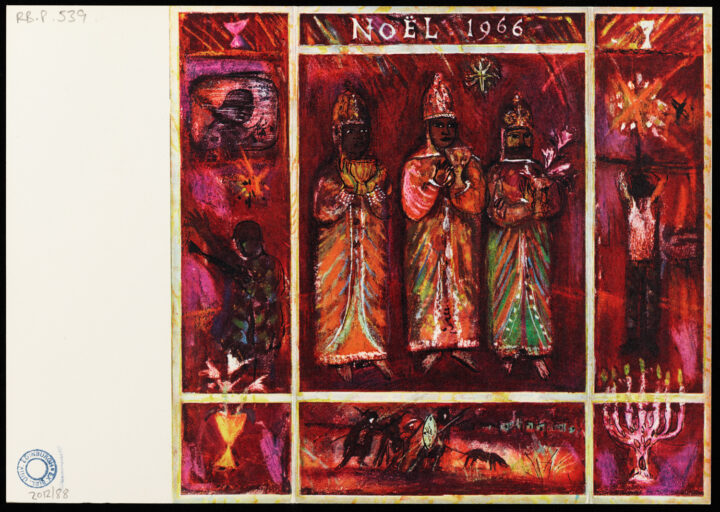

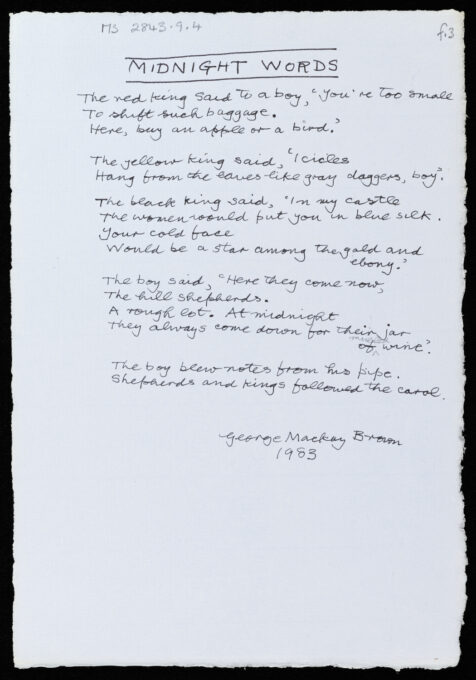

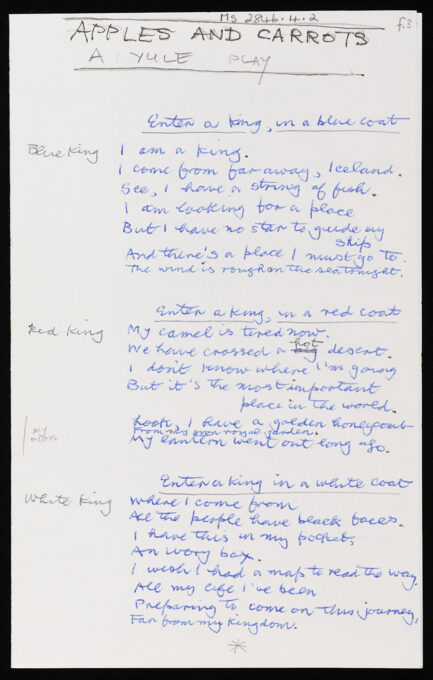

We should like to thank the Estate of George Mackay Brown for permission to exhibit George Mackay Brown manuscripts. We should also like to thank the artists John Lawrence and Rosemary Roberts for permission to exhibit their work, and the Estate of David McClure for permission to exhibit 'The Three Kings'.

Research for the exhibition drew extensively on Dr Linden Bicket's monograph George Mackay Brown and the Scottish Catholic Imagination (Edinburgh University Press, 2017). We should like to thank Dr Bicket for recording a video introduction to the exhibition.

See George Mackay Brown Papers for more information on Edinburgh University Library's major collection of George Mackay Brown manuscripts.

This exhibition was made possible through the support of the Digital Imaging Unit (DIU). The DIU supports learning, teaching and research through the digitisation of and long-term digital access to rare and unique research collections acquired or created by the University of Edinburgh.