Investing in Colonialism

Hampered by tropical disease and imperial rivalries, the colony of New Caledonia ultimately failed, while the effects of the Company of Scotland’s collapse in 1707 on Scottish economics and politics were profound.

Historically, the Company of Scotland has been viewed as a disaster for Scots rather than as a project of colonisation that, if successful, would likely have led to the displacement of the Indigenous people of Darien, and the transatlantic trafficking and enslavement of African peoples.

Company directors and colonists keenly supported the idea of using enslaved labour. One of the Company’s ships scouted the Gold Coast (today’s Ghana) for a suitable place to establish a trading port through which to traffic enslaved Africans, and two Company vessels did transport enslaved people across the Indian Ocean.

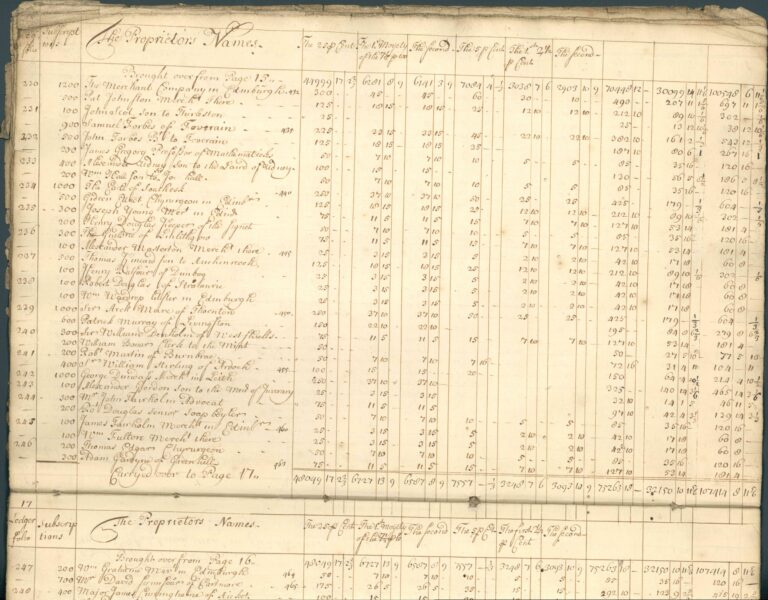

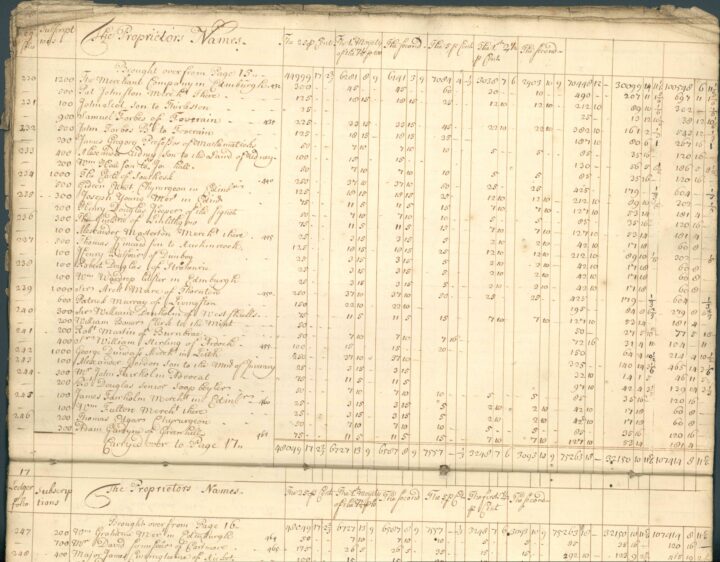

Main image: List of the subscribers in the Company of Scotland trading to Africa and the Indies, NatWest Group Archives D/13 p.16.

This is the Coat of Arms of the Company of Scotland. It illustrates visually the Company’s promise to enrichen its directors and investors. Images of a ship, a llama, a camel, and an elephant emphasise the Company’s aim to forge global trading links with the Americas, Africa and Asia. The motto, Qua panditur orbis vis unita fortior, broadly translates to ‘Where the world expands its united strength is stronger’.

The depiction of figures on either side of the image representing an Indigenous American and an African – each holding horns of plenty, symbolising abundance – speaks to how the subjugation of Indigenous American and African people was integral to the Company’s plans.

|

Guna Yala is how Dule(s), the territory’s Indigenous and sovereign inhabitants, call the land which the Scots attempted to colonise. Dule people refer to themselves as Gunadules. Guna means surface of the Earth and Dule means person, so the term literally translates as a person who inhabits the surface of the Earth.

Marginalised, exoticised and dehumanised in European narratives, the Gunadule claim a rich culture and historic and continued sovereignty over their territory. Despite colonial incursions since the sixteenth century, the Gunadule remain a living, thriving bi-national people. There exist approximately 90,000 Gunadule people in Panamá, who live mainly in the indigenous comarcas (districts) of GunaYala, Madungandí and Wargandí, and 2,000 in Colombia, in the Gulf of Urabá, Necoclí (Antioquía) and resguardos (reserves) of Caimán Nuevo and Arquía (Chocó).

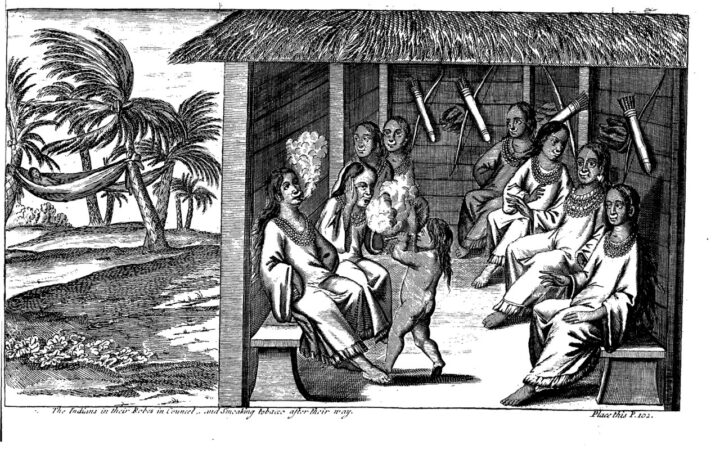

In 1681, Lionel Wafer, a Welsh ship’s surgeon, briefly lived with the Guna-Dule, who helped him recuperate following a gunpower accident. Wafer included this illustration of the Gunadule into an account of his time in Darien, first published in 1699. Replete with descriptions of Darien’s biodiversity and gold as well as its Indigenous people, Wafer’s narrative was read by Company of Scotland directors in Edinburgh.

|

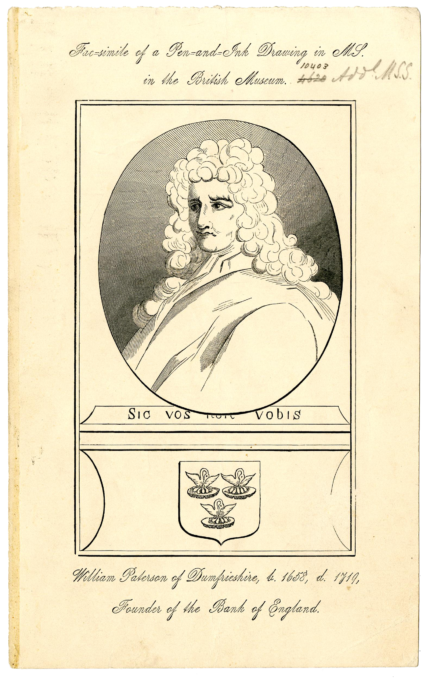

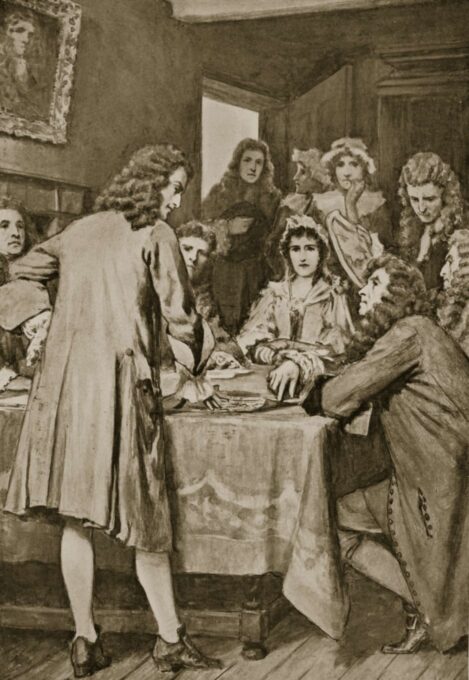

The London-based Scottish banker, merchant and ‘projector’ William Paterson (1658-1719), pictured here, was a major force in devising and encouraging the Darien ‘scheme’ in Scotland. A co-founder of the Bank of England, Paterson had earlier conceived of the idea of colonising Darien while working in the Caribbean.

In 1696, Paterson and other Company directors invited Scots from across the country to invest funds in the Company of Scotland. They did so by signing a ‘subscription’ book in either Glasgow, Ayr or Edinburgh – in the latter case, on High Street, a short walk from the ‘Tounis College’ (later known as the University of Edinburgh).

|

Some members of the University of Edinburgh invested in the Company of Scotland. These included:

- Robert Cheislie, Lord Provost of Edinburgh and Rector of the University;

- Alexander Rule, Professor of Oriental Languages;

- James Gregory, Professor of Mathematics;

- William Scott, Professor of Philosophy;

- and James Gregory, Student of Medicine.

Here is a subscription book where you can see the subscription of James Gregory, ‘Professor of the Mathematicks’ (sixth row from top). His £200 subscription was worth around four times his fixed annual salary.

|

Members of the University of Edinburgh were not unique in developing ties to the Company of Scotland. Subscriptions came from across Scotland; from landowners and aristocrats to the middle classes. Members of other educational institutions in Edinburgh and across Scotland who invested included James Martine, Regent of the College of St. Andrews; Thomas Darling, teacher at Edinburgh Grammar School; Dr Robert Trotter, on behalf of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh; and William Dunlop, Principal of the College (later University) of Glasgow. Dunlop, who had earlier been active in the Carolina Company's Stuarts Town colony, where he had traded in enslaved people, became a director of the Company of Scotland.

|