The work of Edinburgh phrenologists excluded Black people from narratives of civilization and progress. Not everyone agreed with phrenology and these racist theories did not go unchallenged by Black scholars, both in Edinburgh and beyond.

Mind Shift

Confronting a colonial collection

The University's Anatomical Museum holds one of the largest and most historically significant collections relating to phrenology in the world. Now discredited, phrenology was a science of measurement which promoted a colonial agenda, situating Edinburgh as a centre for scientific racism in the 19th century.

This exhibition, of life and death masks, models, artworks and human remains, spotlights contemporary historical, scientific and artistic research into this colonial collection.

What is Phrenology?

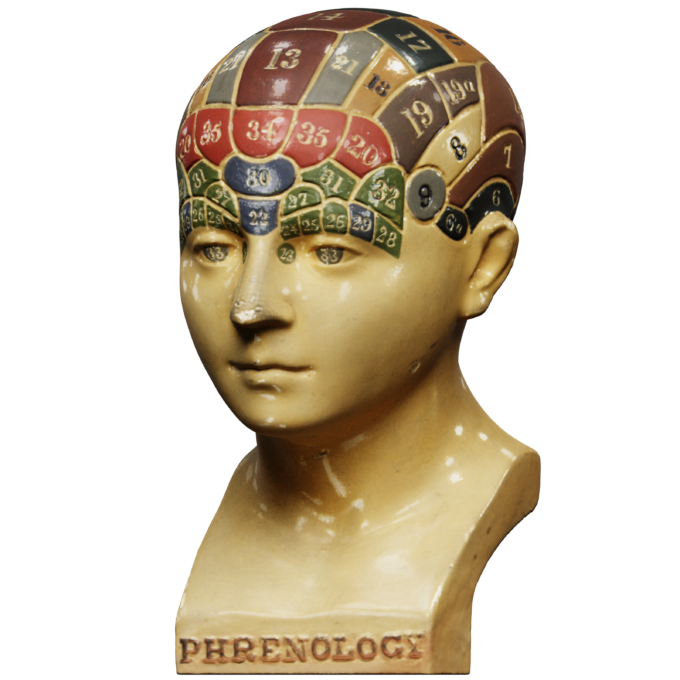

Derived from the Greek words φρήν and λόγος meaning “mind” and “knowledge”, phrenology involved the study of bumps and hollows of the skull, believing they indicated a person's character, personality, or intelligence. The differently-coloured regions on this model are numbered to correspond to areas of the brain that were thought to have certain attributes relating to instinct, sentiment, perception and reflection.

Press ‘Full Information’ below for the qualities that phrenologists associated with each region.

|

Societies and their Collections

Phrenological societies collected life and death masks, skulls and skull casts from individuals across society to support their theories. These included famous authors, politicians, and military figures, as well as known criminals, people of different races, or people with mental illness. Confirmation bias often reinforced their theories but, in some cases, analysis was not what the phrenologists expected.

Use the arrows to explore a selection of masks and casts from the collection.

|

|

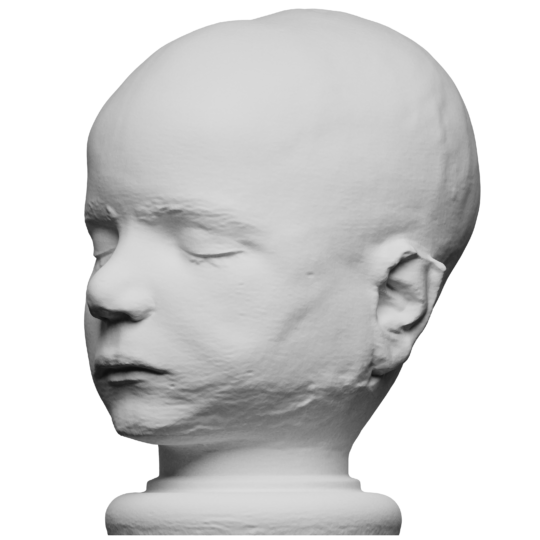

Bell was executed aged fourteen as punishment for killing another child. After his death, phrenologists made this death mask and his body was given to the surgeons of Rochester for dissection. Murderers like Bell were thought to have pronounced organs of destructiveness (the instinct to kill) and underdeveloped organs of benevolence (the sentiment producing kindness).

|

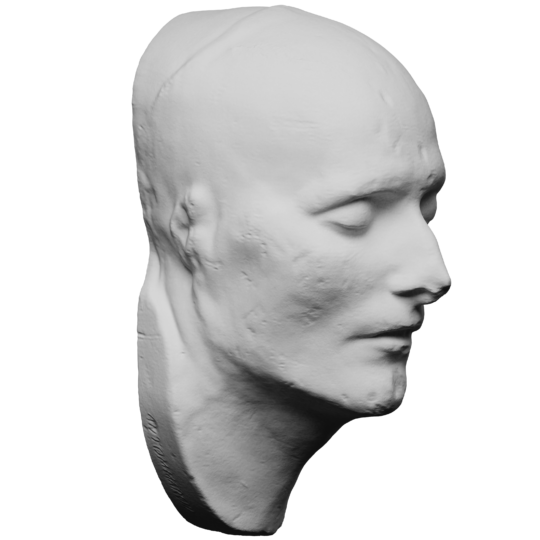

Ornithologist, artist, and a strong believer in phrenology, Audubon’s major work The Birds of America (1827-29), a colour-plate book, is still considered one of the finest works on ornithology ever produced. Phrenologists asserted that his "Organs of form, size, weight, colour, sociality and individuality – the principle observing faculties, most necessary to a painter, are all well developed".

|

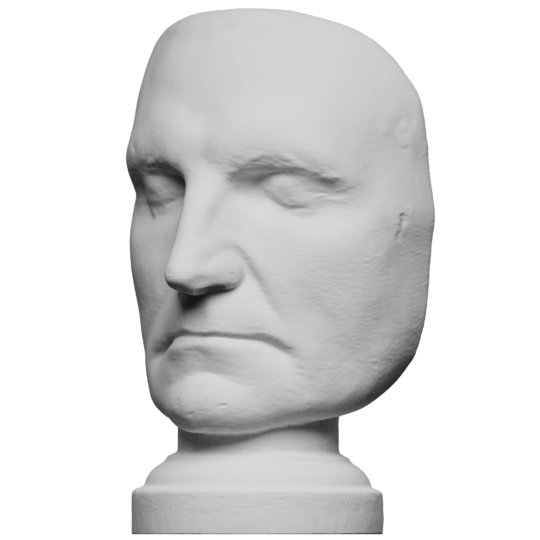

Bonaparte was a French military and political leader. He was a critic of phrenology: "it is an ingenious fable, which might seduce the gens du monde [fashionable people], but could not stand the scrutiny of the anatomist". His death mask was prepared by his physician François Carlo Antommarchi (1780-1838). Napoleon’s phrenological reading was not particularly complimentary: "A precise and sensible mind, but little capable of high conceptions.. On the whole, a sound, well-developed intelligence, but nowise approaching to genius: general aptitude for a variety of subjects, but only to a feeble degree".

|

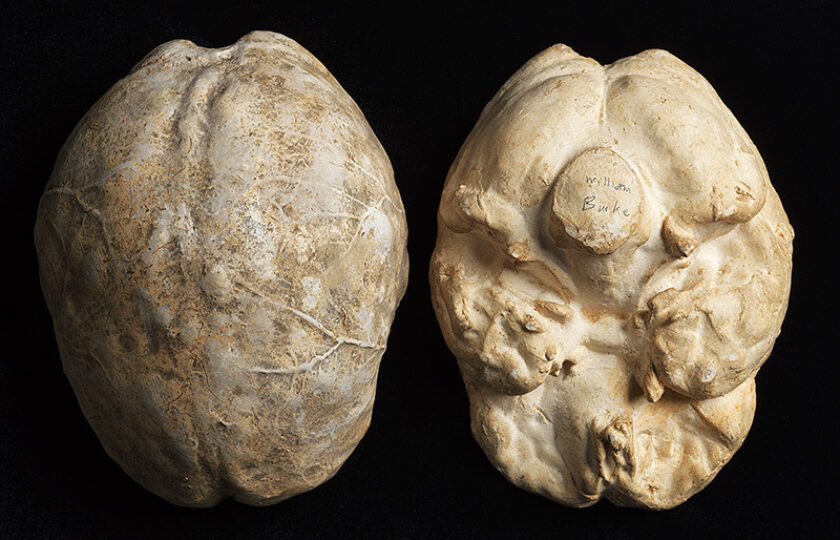

Burke and William Hare murdered 16 people to supply cadavers for dissection to the Edinburgh anatomist Dr Robert Knox. Burke's hanged body was dissected by Professor Alexander Monro tertius and his skeleton became part of the Anatomical Museum collection. The analysis of his brain surprised the phrenologists. Burke’s organ of destructiveness (the instinct to kill) was not well developed, while his organ of benevolence (the sentiment producing kindness) was larger than expected.

Phrenology in Edinburgh

Already a historically significant and leading city for the teaching and advancement of Western medicine for over 400 years, Edinburgh became the principal centre for the study of phrenology in Britain in the 19th century.

While not officially taught as an academic subject, phrenology was supported and discussed by several influential figures in science and medicine whose close connections with the University gave it legitimacy and prestige.

Uses the arrows to learn more about some of these supporters.

|

George and Andrew Combe, brothers from Edinburgh, were both educated at the University. George became a firm believer in phrenology after attending a lecture by Johann Gasper Spurzheim, one of phrenology’s founders. The brothers founded the Edinburgh Phrenological Society in 1820 and a museum was set up to display their growing collection of life and death masks.

|

In 1887 Sir William Turner arranged the transfer of the Edinburgh Phrenological Society’s original collection into the newly built medical school and museum at Teviot Place. Previously a senior demonstrator in the department of Anatomy for 13 years, Turner succeeded Sir John Goodsir as Professor of Anatomy in 1867, eventually becoming the University’s Principal in 1903.

Most of the skulls in the Anatomical Museum today were assembled by Turner. Craniology, which involved measuring the angle of the face, the size of the braincase, or the ratio of the length to the breadth of the head, were used by academics like Turner to classify people into racial groupings, to make claims about alleged differences in intelligence, and to study human variation. Because of its prominence in Britain and abroad, skulls continued to be sent to the University into the early 20th century to formulate racist theories in other fields.

|

Over the course of the nineteenth century, many University graduates wrote about and discussed the subject of phrenology, including George Murray Paterson, the Scottish physician and surgeon for the East India Company; John William Jackson, an anthropologist and Fellow of the Anthropological Society of London; and Sir George Steuart Mackenzie, a geologist, chemist and agriculturalist. Two former medical students, in particular, had significant, albeit different, impact beyond Edinburgh.

Samuel George Morton, an American physician and anatomy professor, trained at the University until 1823. Influenced by phrenology, Morton is regarded as the founder of "American School" ethnography which claimed the difference between humans was one of species. Morton’s work was referenced by phrenologist James Hunt, who published a pamphlet during the American Civil War arguing that Black people were intellectually inferior to Europeans and destined to remain in the subservient positions that Morton’s work described.

Charles Darwin considered Morton an authority on the subject of race. As a student between 1825 and 1827, a young Darwin participated in phrenological discussions at the Plinian Society, a University club for students interested in natural history. He made this observation in the same notebook as his groundbreaking theories about natural selection: "One is tempted to believe phrenologists are right about habitual exercise of the mind altering form of head, & thus these qualities become hereditary." Charles Darwin (1838) The M Notebook.

The Abolitionist

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in Maryland, USA, but went on to become a famous public speaker, philosopher, intellectual and self-liberated freedom fighter. A frequent visitor to Edinburgh between 1845 and 1847, he campaigned across Britian and Ireland against slavery for freedom and social justice.

Douglass was acquainted with phrenology in Edinburgh, visiting George Combe alongside abolitionists George Thompson and William Lloyd Garrison and reading Combe’s Constitution of Man. In 1854, Frederick Douglass hit out at phrenology, arguing that in their comparisons phrenologists “invariably present the highest type of the European, and the lowest type of the negro.” Once again linking phrenology directly to slavery, Douglass concluded “by making the enslaved a character fit only for slavery, they excuse themselves for refusing to make the slave a freeman.”

Douglass is also one of the inspirations behind the artist's commission for this exhibition: Tayo Adekunle's Fitting the Character.

|

Edinburgh's First African Graduate

James ‘Africanus’ Beale Horton was born in Sierra Leone. Following the British War Office’s idea to train Africans in medicine, Horton was among the first Africans to be sent to Britain to study for a medical degree in 1853.

Around a third of Horton’s 1868 work, West African Countries and Peoples, British and Native: and a Vindication of the African Race, is dedicated to the discussion of race, anatomy, and phrenology. In his book he challenges the phrenologist James Hunt by name, whose pamphlet he says contains “tissues of the most deceptive statements, calculated to mislead those who are unacquainted with the African race... his descriptions are borrowed from the writings of men who are particularly prejudiced against that race; his absurd pro-slavery views, as contained in his pamphlet, would have perhaps suited a century ago; but all true Africans must dismiss them with scorn”.

Phrenology may have been debunked over 150 years ago, but its foundational theories continued to have impact, even today.

Phrenology deeply influenced the development of modern anthropology, criminology, and evolutionary biology as well as eugenics which further encouraged skull-collecting activities as the British Empire grew. Discover more about the role of skull collecting in the next section.