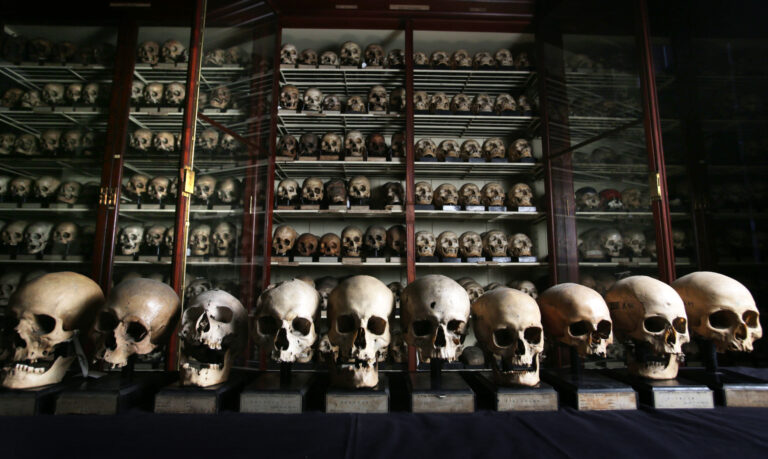

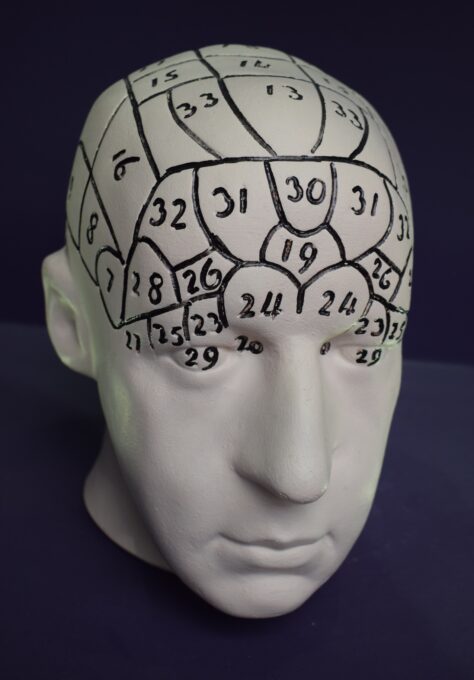

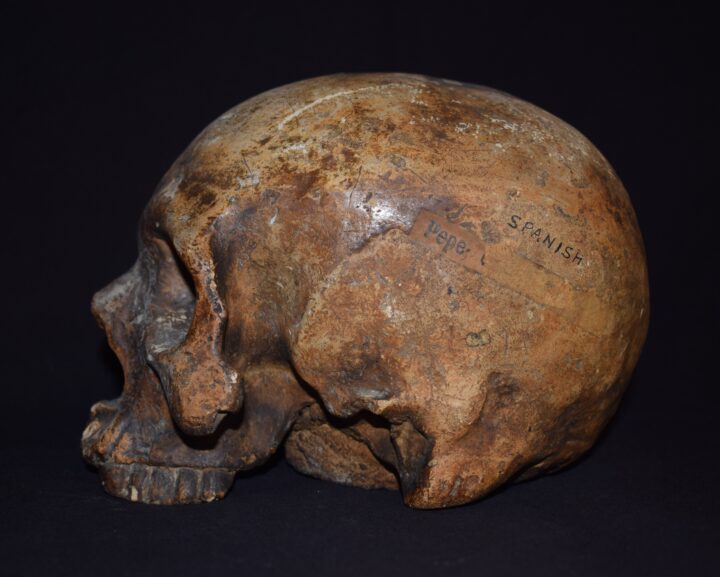

This exhibition spotlights the work of academics, curators, students and artists to uncover and confront this colonial collection over the past decade, but this work is incomplete. New projects continue to dig deeper to understand the impact of phrenology in Edinburgh and abroad, and its lingering influence in other racial sciences.

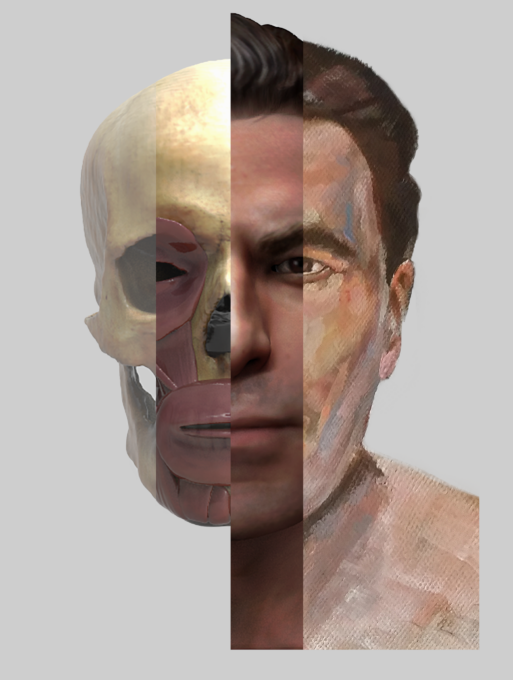

In the next section, you can explore an artist's response to this exhibition and collection by Tayo Adekunle.

You can also discover more information about ongoing research with the collection at the University on the Anatomical Museum’s blog.