Sea Change

Celebrating the groundbreaking expedition of HMS Challenger

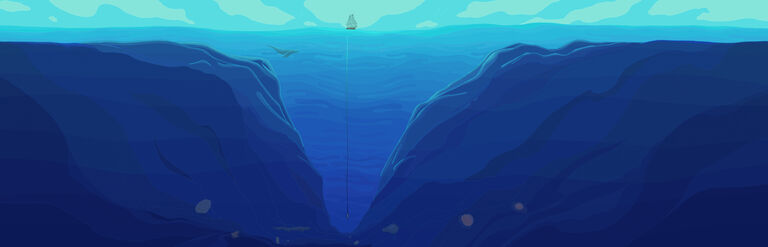

Just over a century before NASA’s Space Shuttle Challenger made its maiden flight in 1983, its namesake embarked on a groundbreaking voyage of exploration across the world’s oceans.

Circumnavigating the globe between 1872 and 1876, the crew of HMS Challenger collected data and specimens to help us understand the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of the deep sea. Published over 20 years from the expedition’s offices in Edinburgh, the Challenger Report would become the first detailed record of our oceans, providing baseline data for the effects of climate change on our oceans today.

From ship modifications to cutting edge instruments, new scientific and publishing practices and the role of imperial and trade networks in 19th century research expeditions, this exhibition explores the global, technological, and social changes that laid the foundations for modern oceanographic studies.

While the expedition departed on its voyage under the command of Captain George Strong Nares (1831- 1915) from Sheerness, England in 1872, its story begins in 1871. Charles Wyville Thomson (1830-1882), Professor of Natural History at the University, and William B. Carpenter (1813-1885), Registrar of London University and vice-president of the Royal Society, successfully persuaded the Royal Society of London to ask the British Government to supply a ship for a prolonged voyage of exploration.

Thomson served as the scientific director on Challenger, building on his successful work aboard HMS Lightning and HMS Porcupine for deep-sea expeditions in the summers of 1868 and 1869 where he and Carpenter confirmed the presence of life at great depths.

|

||||

| Object reference | Gen.30.3 |

|---|

Joining Thomson on the expedition was the chemist John Young Buchanan (1844-1925), the artist John James Wild (1824-1900), and three naturalists including John Murray (1841-1914), a student at the University who would later be regarded as the father of modern oceanography.

Murray was second in command at the Challenger Office in Edinburgh when the expedition returned but became director after Thomson’s death in 1882. He dedicated over two decades of his life to the project, from assisting Thomson during the voyage to overseeing the final publication of the Challenger Report, including his own significant report on deep-sea deposits.

|

||||

| Object reference | Coll-46 |

|---|