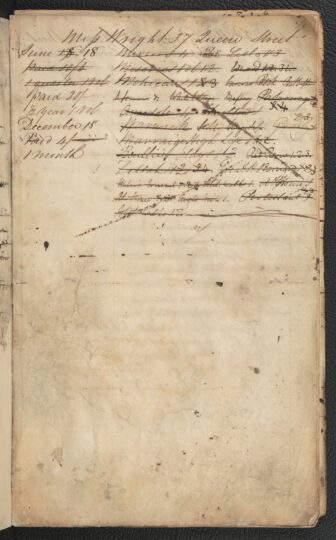

Library Registers

Library borrowing registers can take various forms, from simple lists to pre-printed pages where the details about the book and borrower are added.

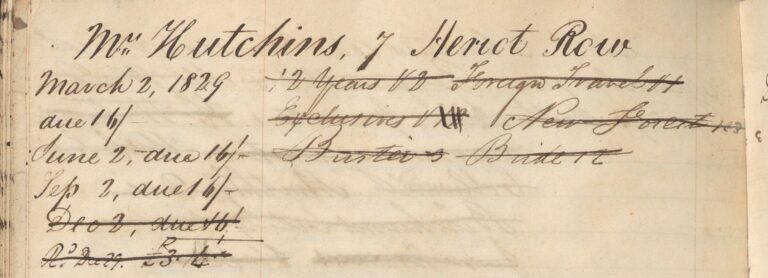

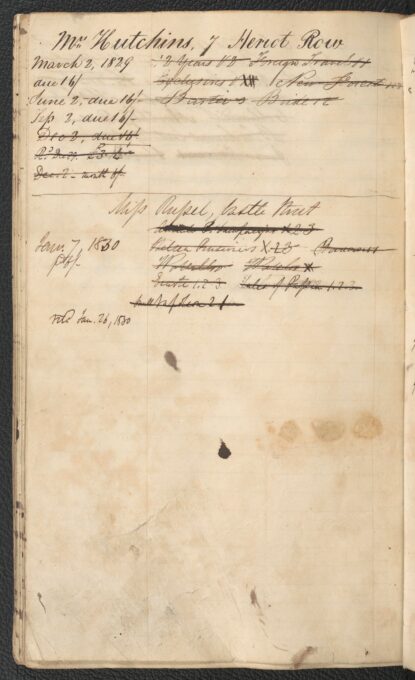

Image: Detail of Mrs Hutchins’s Chambers’ Library Borrowings, 1829, National Library of Scotland

© Chambers family. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Licence

Borrowing registers tell us who borrowed which books and when. The period 1750 to 1830 enables investigation of two movements of historical and literary interest: the Scottish Enlightenment and Romanticism. Collecting and interpreting the data stored in borrowing registers shows who used libraries and what books were popular. Scottish borrowers’ registers, thanks to a high literacy rate in the period, enrich our knowledge of the histories of books and reading by revealing the use of libraries by a wide cross-section of the population.

Click the arrows to explore examples of borrowing registers from four Edinburgh libraries.

|

||||||

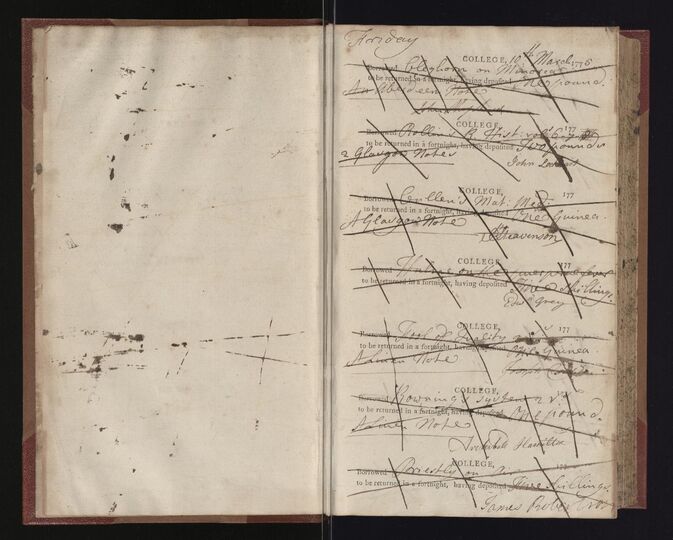

| Object reference | University of Edinburgh: EUA IN1/ADS/LIB/3/Da.2.11 |

|---|

The University of Edinburgh was the largest in Scotland and one of the most important in the western world in the late eighteenth century. Its students included future law clerks, parish schoolmasters, ministers, and surgeons who studied classics, philosophy, and natural sciences alongside their courses in divinity, law, and medicine. Medical students formed the largest group and their borrowings provide evidence for their preparation for practice in the growing British Empire with texts on scurvy, tropical diseases, and gunshot wounds being among the most popular titles.

|

||||||

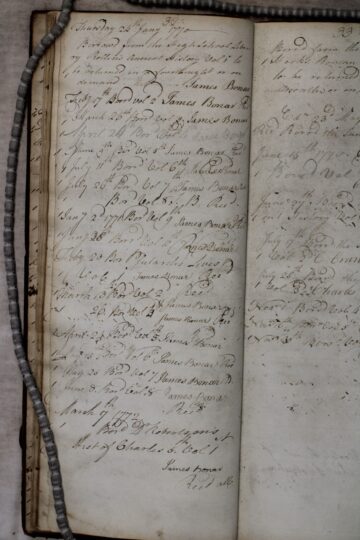

| Object reference | Royal High School of Edinburgh, SL137141, f. 32 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit / Usage information | © Edinburgh City Archives |

The Royal High School’s borrowing register shows changes in educational practice inspired by Enlightened thinking. The purely classical education focussed on Latin and Greek that dominated until the late eighteenth century widened to encourage reading in a broader range of subjects. Books for entertainment joined academic texts with stories of voyages and travels the most popular with the school’s child readers.

Many pupils, like James Bonar, continued their education at the University. Bonar worked in the Edinburgh excise office in 1788 where he discovered the notorious Deacon Brodie’s attempted robbery.

|

||||||

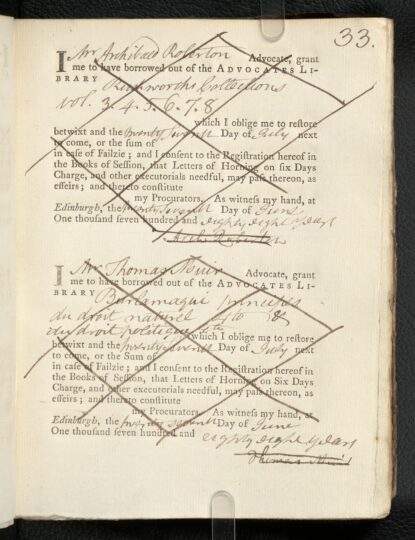

| Object reference | FR262a-15, p. 33 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit / Usage information | Reproduced by kind permission of the Faculty of Advocates and the National Library of Scotland. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Licence |

Scottish advocates were at the centre of Edinburgh’s cultural and social elites. They participated in Enlightened debates at social clubs and wrote important works of history, philosophy, and jurisprudence. They provided reviews, articles, and editorials for influential new periodicals. Their borrowings provide evidence for both their legal work and their other intellectual activities as they refined Enlightened arguments and critiqued Romantic literature and ideas. Their library was a sociable space as well as a repository for learning.

|

||||||

| Object reference | National Library of Scotland MS Dep. 341/413, p. 17 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit / Usage information | © Chambers family. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Licence |

Our other featured libraries were limited to particular groups of male pupils, university students, or advocates, but Robert Chambers’s Circulating Library was available to anyone who paid a subscription, including women. This was one of many circulating libraries in Edinburgh in the 1820s, but the survival of its ledger is unique. The Chambers register records subscriptions paid and borrowers’ addresses as well as their borrowings. It shows the residents of Edinburgh’s New Town as avid consumers of literary culture, including novels and periodicals.

|

Edinburgh students were enrolled in mid-December. Upon payment of their fees, they received a printed ticket saying 'Civis Bibliothecae Academicae Edinburgenae' that confirmed their membership of the University Library for the coming year. Students could borrow books for a fortnight on payment of a deposit equal to the value of the book. This was refunded when the book was returned. The University Library's borrowing registers are called 'receipt books' since they record financial transactions of borrowing alongside bibliographical and borrower information.

Charles Darwin (1809-1882) enrolled at the University of Edinburgh to study medicine in 1825, aged 16. He left without graduating two years later having undertaken natural history studies that influenced his career as a naturalist.

|

Subscribers to Robert Chambers’ Circulating Library selected borrowing packages based on price on annual, half-year, quarterly, or monthly terms. Options ranged from a ‘NEW BOOKS’ subscription which gave ‘the Privilege of getting the Earliest Reading of every New Publication, periodical or otherwise, Three Volumes at a time’ to an ‘OLD BOOKS’ subscription which allowed ‘Three Volumes at a time of any Book upwards of three years old’. Subscribers had access to periodicals including the Quarterly, Edinburgh, Westminster, London, and Foreign Quarterly Reviews.

Click 'Full Information' below to discover what the subscriptions cost in 1829.

|