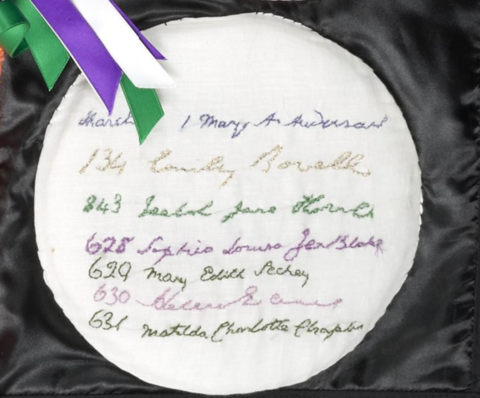

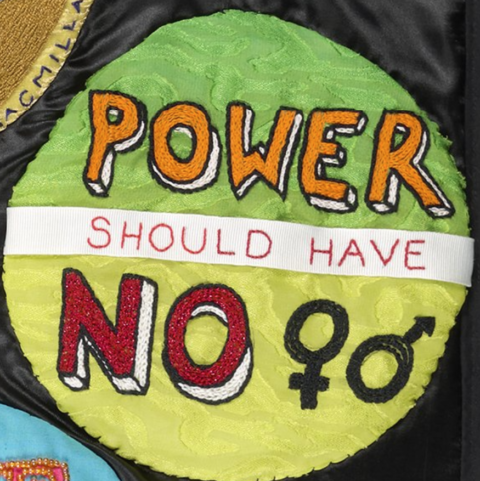

The Processions Banner was created by a collaborative network of 100 female artists, in preparation for the 2018 march that celebrated 100 years of women’s suffrage. It is a composite piece, featuring over thirty embroidered and appliqued roundels that were made by different contributors. The roundels include portraits of several famous women – Emily Pankhurst, Frieda Kahlo and Malala Yousafzi – in addition to a number of political slogans and inspirational messages. One roundel also features the embroidered signatures of the Edinburgh Seven, the first female students to matriculate at any British university, who began their studies at the University of Edinburgh in 1869. The Edinburgh Seven were later denied the right to graduate and to practice medicine following widespread outrage and intervention from Scotland’s Court of Session.

The Textiles in Focus

This exhibition brings together five items from the University Collections which delve into women’s use of textile production as a means of engaging with personal and political struggle in the 20th and 21st centuries. The goal of Voices of Textiles is to start conversations and to celebrate collaboration within community. Each new textile object and artwork explored below lends a voice to the conversation, and each question asked adds a new thread to the loom.

The Fashionable Protest

This belt was likely owned by an active Suffragette. The oxidisation and repairs on the reverse side indicate that at some point it has been reduced in length. This implies that it has been owned or worn by multiple women, providing physical evidence of the network of Suffragettes who openly and proudly advocated for women’s voting rights and equality. In addition, the smallest point of its multiple stages of repairs indicate that it may have been worn by a child; the movement for female suffrage and equality was (and still is) multi-generational, forming a close-knit community of like-minded women.

The Suffragette Belt embodies an interesting dissonance. The physical nature of a belt is constrictive and constraining, intended to secure a dress to a body. However, the Suffragette movement personifies the female voice, mobilisation, and liberty, and its intent is the very opposite of binding. The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed dramatic changes across the globe. In the heart of all this momentous change, the unified fight for women's rights intensified and became known as the Suffragette Movement.

This beautiful and intricate belt design reclaims the oppressive boundaries that the Suffragette movement rallies against, personalising and politicising a simple and functional garment until it becomes a work of art in its own right.

|

||||

| Object reference | EU4277 |

|---|

|

||||

| Object reference | EU4277 |

|---|

In January of 2017, former United States President Donald Trump passed Executive Order 13769, ‘Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States’. People around the world responded in condemnation, including then Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) student Elle McKee. The artist designed a set of printed silk scarves to protest Trump's decisions, and to show solidarity with the countries impacted under the Travel Ban. This project, titled Banners of the Banned, became a keystone of her final degree showpiece and won the University of Edinburgh Art Collection Acquisition Award, 2017.

The banners are printed silk scarves, inspired by the national flags of seven countries with immigration restrictions. The scarves draw together common colours, shapes, and patterns from the flags of Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen, creating a set of seven beautiful and vocal garments. Mckee also received inspiration from a wide range of colours, cultural symbols, architecture, and designers, all originating from the histories of the nations affected by the ban. Using these outside influences and the flags, she created unique and bold pieces, that still weave together narratively.

Banners of the Banned, created over a century after the Suffragette Belt, highlight textiles’ continuing presence in women’s political lives. In an image-obsessed and visually critical culture, poignant symbols of defiance, unity, and conviction enduringly vocalise political allegiances and beliefs. The idea of a fashionable accessory representing a steely resolve is an unusual one. The Banners of the Banned are a set of soft and delicate silk scarves with a pointed political message, embodying the idiomatic phrase "an iron fist in a velvet glove".

|

A Community of Women

The women featured in this painting are waulking the cloth – that is, beating it against the table to lightly felt it, which helps it to shrink and repel water. Although the cloth here is pale and light, this method would also have been used to prepare tartans and plaids. Waulking requires immense communication and cooperation, for if the lengths of cloth are kneaded out of time they can become overstretched and damaged. To keep them in unison, Scottish women often sang; one woman would lead the verse, with her companions joining in for the choruses. Depending on the width, length, and thickness of a piece of cloth, the singer could add in or omit verses. The cloth would enter the community twice over; not only would women be brought together during the production process, but they were also the ones who would primarily fashion raw cloth into clothing, providing for their families.

|

This song is titled ‘O Ho Hio Hao Ri Iù’, and tells the tale of a woman on a sea journey. She is greatly distressed, for her brothers have recently died from battle injuries despite her efforts to care for them and to cure them. Women waulking the cloth to this song would have soaked, kneaded, and passed along plaid fabric, whilst singing about bringing their wounded family water, and resting their heads on folded plaids.

|

This song best evidences the communal call and response of the typical waulking song. It is titled ‘Bidh an Deochs’ air Làimh Mo Rùin’, and it discusses another young woman journeying far from her home. This was a common theme in waulking songs; whilst they worked and labored in community spaces close to home, they could escape and explore through their songs.

|

The Power of a March

This banner is one of an identical pair made as part of Petra Bauer and SCOT-PEP’s film Workers!, commissioned by Collective. While one banner was acquired by the University’s Contemporary Art Research Collection, the other remained with SCOT-PEP for use as part of their sex worker rights activism. The banners are double-sided; when part of a procession the dawn side faces forwards and dusk faces back towards the marchers. Both incorporate two red umbrellas (the international sign of the sex worker rights movement) and the slogan ‘Sex Workers UNITE’ in a font reminiscent of a neon advertising sign; they are unapologetically assertive.

To listen to Glasgow-based artist Fiona Jardine talk about the process of commissioning and designing the SCOT-PEP banner, click here.

|

In addition to their striking visual appearance, the banners are both eminently functional; they were fabricated using lightweight materials, and a series of loops and ties adorn three sides, allowing them to be carried and displayed with ease. The banners were debuted at the 2018 May Day march in Glasgow, where SCOT-PEP and the Sex Worker Advocacy Resistance Movement (SWARM) sought to raise awareness of abuse and exploitation under current sex work criminalisation laws, and to demand protection against deportation for migrant sex workers.

|

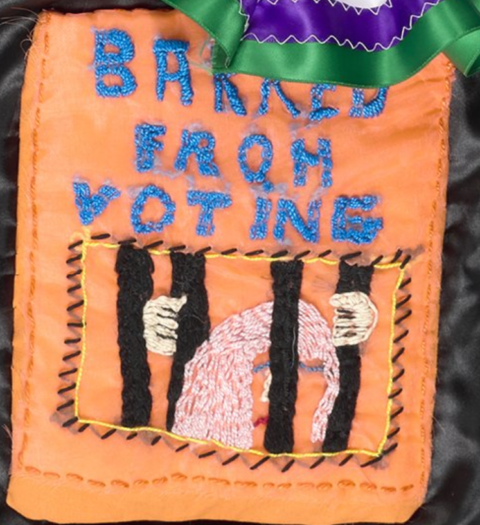

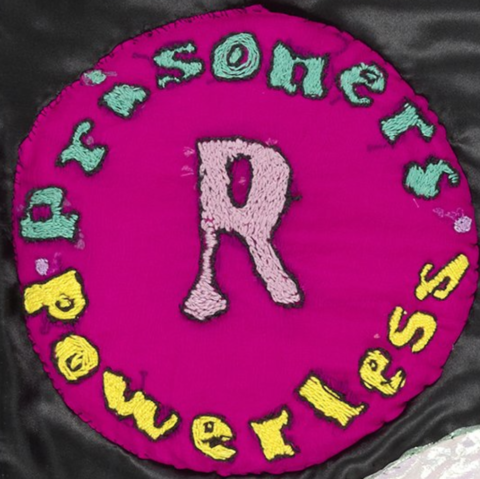

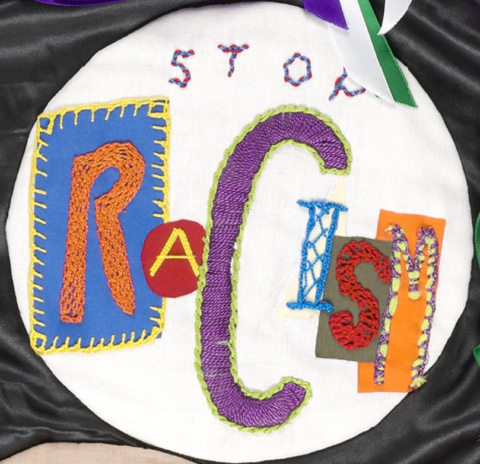

The roundels that adorn the banner are unapologetically political. By featuring the message “EVERY ONE IS EQUAL” in the purple, green, and white of the suffragettes, the very idea of equality and equal rights to participate in society become politicised. The pointedly political motifs are also united with basic equality through their proximity and deliberate inclusion to such reasonable and open-hearted messages. ‘Dump Trump’, ‘Let prisoners vote’ and ‘sisters not cisters’ are depoliticised and destigmatised by being voiced alongside slogans such as ‘equality is everyone’s responsibility’ and ‘support each other’, because the only alternative would be to insinuate that equality and support are a political decision rather than a moral responsibility. Through this piece of art, political expression becomes beautiful, aspirational and achievable, rather than being touted as a liberal ideal that could never come to fruition.

Explore the banner by clicking on the eye in the upper right-hand corner, or by exploring the highlighted roundels below.

|

||||||

| Object reference | EU5661 |

|---|