Bastions Stormed

Bastille-like buildings, symbolic of an established order or an old faith, are attacked and devastated by revolutionary forces in many of Scott’s novels.

In the works depicting revolutionary moments, and in other novels in his Waverley series, Scott repeatedly presented his readers with scenes that had immediate contemporary resonance.

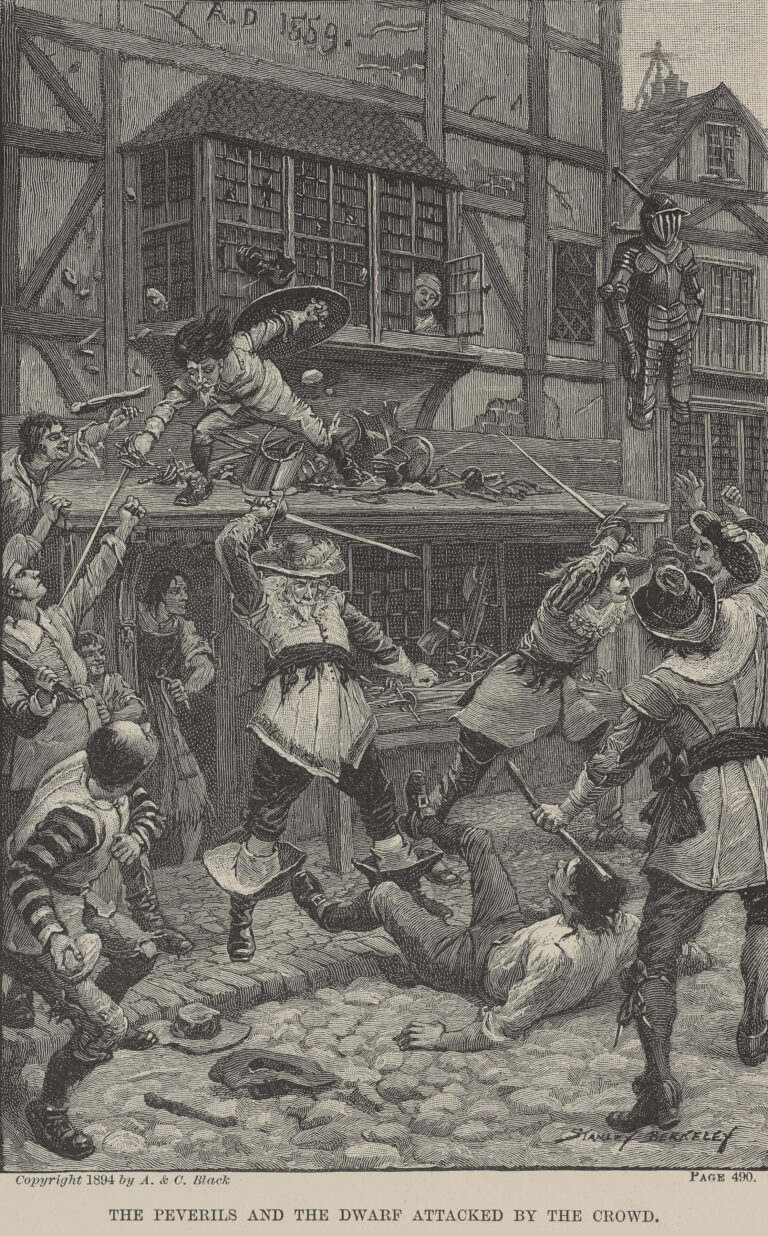

Many of Scott's novels portray instances of mob violence. While violence is chiefly triggered by tyranny or neglect, these outbreaks are often shown to be instigated or manipulated by middle-class agents, whose revolutionary idealism is always tainted by self-interest.

Where unrest evolves into regional or national rebellions, Scott depicts grand revolutionary battles. He rarely, however, presents a broad overview of a battle from an omniscient perspective. Instead, he uses the partial and confused point of view of an onlooker or isolated participant.

Bastille-like buildings, symbolic of an established order or an old faith, are attacked and devastated by revolutionary forces in many of Scott’s novels.

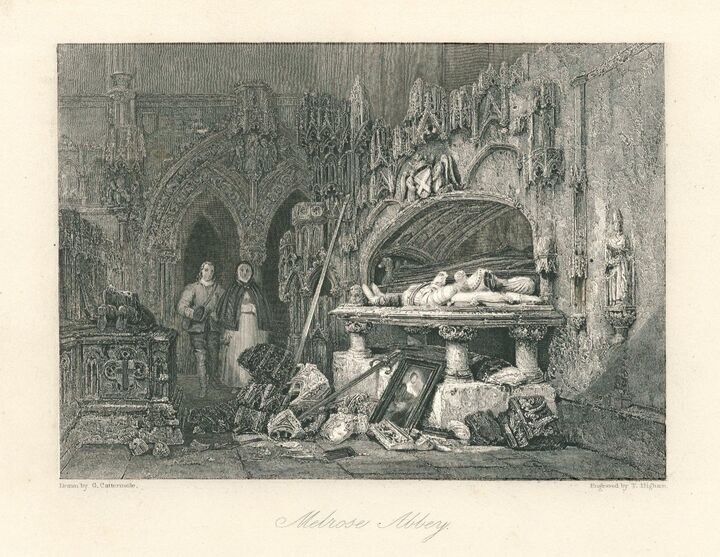

In The Abbot, the hero Roland Graeme and his devoutly Catholic foster-mother, Magdalen Graeme, visit Kennaquhair Abbey (based on Melrose Abbey in the Scottish Borders) after it has been attacked by Protestant Reformers. In his novel, Scott clearly condemns the desecration of a building of both religious and historical value.

He writes: ‘Magdalen and Roland remained alone in that great vaulted space… and in the pell-mell havoc, the tombs of warriors and of princes had been included in the demolition of the idolatrous shrines. Lances and swords of antique size, which had hung over the tombs of mighty warriors of former days, lay now strewed among relics.’

|

Scott’s novels feature assassinations, executions, and acts of extreme cruelty and violence committed for revolutionary ends. Besides recalling the French Revolution and Irish Rebellion, they would have reminded his original readers of the assassination of the British Prime Minister Spencer Perceval in 1812 and of the Cato Street Conspiracy of 1820, an attempt to murder the entire British Cabinet.

As these pictures show, Scott rarely portrays acts of terror or revolutionary justice directly. Instead, he records the tormented feelings of the perpetrators or the reaction of horrified witnesses.

In Scott’s day, British representations of the French Revolution particularly stressed the prominent role played by female revolutionaries. These women were portrayed either as masculine or unsexed, or as irrationally passionate and bloodthirsty. Such depictions revealed anxieties around women entering traditionally male terrain and occupying positions of power.

While Scott was publicly supportive of many female writers, his own novels often reflect the contemporary fear of women breaking through gender boundaries.

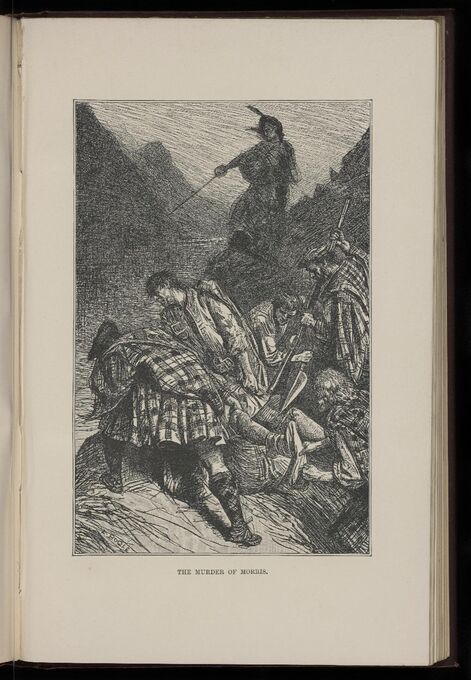

In Scott's novel Rob Roy, the violence with which Rob’s wife, Helen Macgregor, treats representatives of the British government, channels early 19th-century fears about female revolutionaries and female authority in general.

Here, leading the Clan MacGregor in Rob’s absence, she brutally orders the execution by drowning of Morris, a suspected government spy.

|

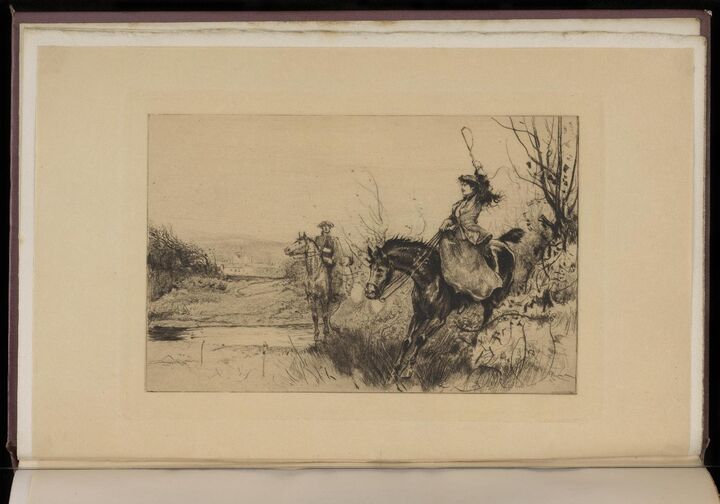

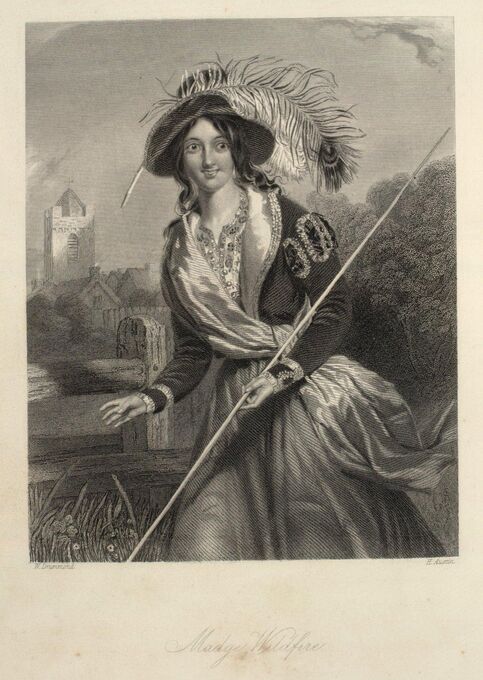

Diana Vernon, the future wife of protagonist Frank Osbaldistone in Rob Roy, also challenges gender norms. Excelling at masculine sports and impatient with the limits of a traditional female education, she intimidates and overpowers Frank. Her relative ‘manliness’ is linked to revolutionary passions, as she helps her father plot the Jacobite uprising of 1715.

This image portrays Frank’s first glimpse of Diana, where he is struck by her unusual riding clothes ‘resembling those of a man’.

|

In Scott’s time, protesters often evoked the upside-down world of carnival through cross-dressing. Male protesters adopted female costume, partly because few other disguises were readily available in working-class households, and partly to signal that economic hardship and political humiliation had deprived them of their true identity.

In The Heart of Mid-Lothian, George Staunton leads the Porteous Rioters disguised as Madge Wildfire, a madwoman who later befriends the heroine Jeanie Deans.

|

Scott’s novels also reflect contemporary fears of secret or sworn societies plotting revolution underground.

In some cases, such societies were real, such as the United Irishmen or the Friends of the People, though the extent of their power and influence were exaggerated, and, in the case of the Friends of the People, they aimed at reform rather than revolution. In other cases, like the Illuminati who were widely blamed for provoking the French Revolution, their activities were largely a figment of the conservative imagination.

The Illuminati were an Enlightenment-inspired secret society formed in Bavaria in 1776 to oppose abuses of church or state power. They were outlawed in 1784 and falsely accused by conservative and religious parties of continuing underground and plotting the French Revolution.

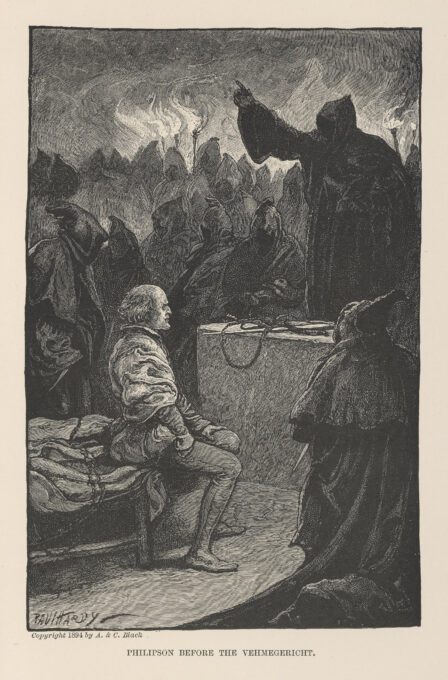

Scott portrays a similar society in Anne of Geierstein (1829), which is largely set in 15th-century German-speaking Switzerland. The Vehmegericht or Secret Tribunal judges and punishes perpetrators of injustice and all those who challenge its power.

In this picture, John Philipson, an exiled Englishman, is on trial before the hooded judges of the Vehmegericht’s underground court who accuse him of defaming the reputation of their society.

|

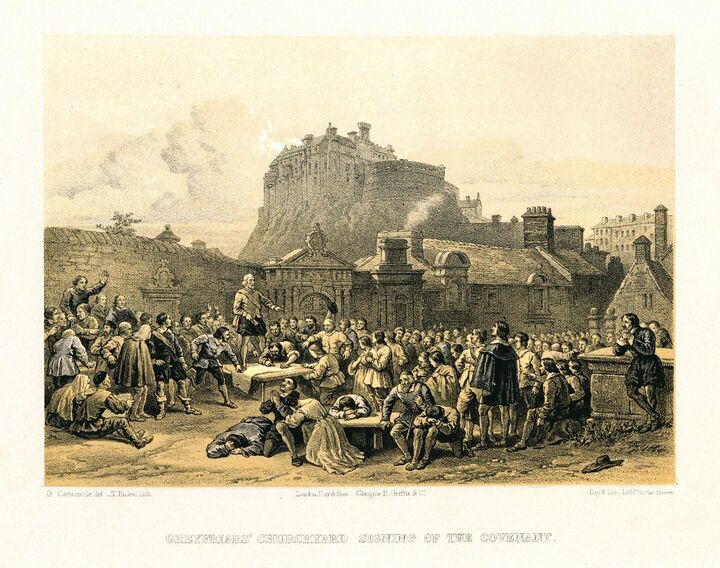

The Covenanters, depicted in Old Mortality and A Legend of Montrose, might also be viewed as a sworn society. The National Covenant was an agreement signed by the people of Scotland in 1638, in opposition to King Charles I’s proposals to reform the Church of Scotland along Anglican lines. Committing its signatories to defend Scotland’s national religion, it was interpreted by Charles I as an act of rebellion, leading to the Bishops’ Wars of 1639-1640.

This image depicts the mass signing of the National Covenant in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh, which began on 28 February 1638, and which Scott describes in Tales of a Grandfather (1828-1830), a history of Scotland for children. Greyfriars Kirkyard also had strong personal associations for Scott. His father and sister were both buried there in the Scott family burial-plot.

|

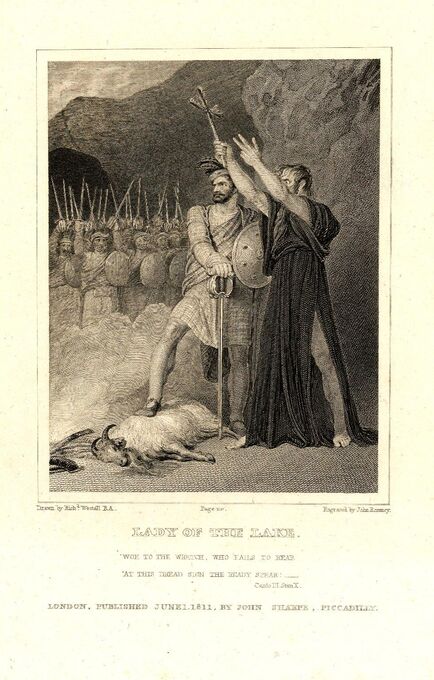

In Scott’s works, Highland clans sometimes resemble secret or sworn societies. In The Lady of the Lake (1810), the lighting of the Cross of Fire is a signal bidding the Clan Alpine to respond to the summons of their chief Roderick Dhu, who launches a rebellion against James V of Scotland.

In drawing a parallel between clans and contemporary revolutionary societies, Scott suggests that revolutionary violence is a throwback to a superseded stage of Scottish history marked by fanatical civil warfare.

|

As a private citizen, Scott voiced strong support for government suppression of radical and reformist activities. In his novels, however, he shows a vivid awareness that an extreme response to civil unrest and a refusal to listen to marginalized voices can only increase the danger of revolution.

The depiction of exiled and displaced monarchs and aristocrats in the Waverley novels again evokes recent events. During the French Revolutionary Wars, exiled French aristocrats were a common sight throughout Britain.

In Scott’s Edinburgh, the future King Charles X of France (Louis XVI’s brother) lived in exile in Holyrood Palace.

Many Scottish landowners of Scott’s day owned property that had been confiscated from Jacobite noblemen who had participated in the 1715 or 1745 uprisings.

Redgauntlet portrays a fictional third Jacobite uprising in 1765. Charles Edward Stuart ('Bonnie Prince Charlie') lands in Scotland but the government is informed of his plans, and the rebellion soon fizzles out. Charles is permitted to return to political exile in Italy, and, in stark contrast to the 1745 Rebellion, his supporters are not prosecuted.

Here Charles is portrayed bidding farewell to his followers before setting sail for Europe.

|

||||||

| Object reference | Coll-1022/CCWS/ILL/P.1833 |

|---|