The Reformation

Scott’s novels The Monastery and The Abbot (both 1820) portray the religious, political, and social turmoil of the Reformation. This 16th-century movement for church reform ended in the establishment of the Protestant Churches of England and Scotland.

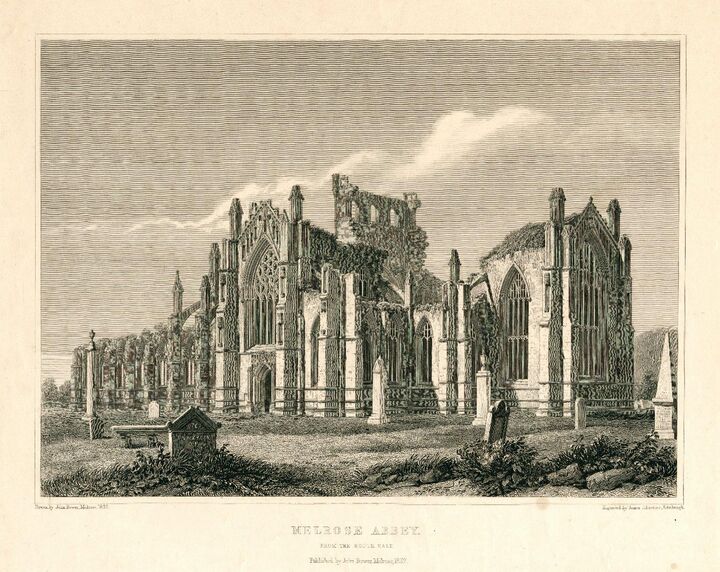

The Monastery sees the monastic community of Kennaquhair (a fictional representation of Melrose Abbey in the Scottish Borders) threatened by the emerging Protestant movement. Its sequel dramatizes the forced abdication of Mary Queen of Scots, her imprisonment in Lochleven Castle, and her escape to England.