Scott’s Revolutionary Influence

At home, Scott’s own political views, as suggested by his novels, struck readers as relatively conservative. Abroad, however, they often appeared revolutionary in themselves. In countries seeking independence from transnational empires, his works were often interpreted as a defence of repressed cultures and languages with a rich historical tradition of their own. In other countries, where the Treaty of Vienna had restored the absolute power of monarchies, Scott was seen as a voice for liberalism.

Everywhere, writers imitated Scott’s innovative brand of historical fiction, using key moments in their country’s past to comment on the present. Often, writers combined literature with political action, playing a leading role in 19th-century Europe’s many revolutions.

The French translator Auguste-Jean-Baptiste Defauconpret is perhaps the most significant agent in the European discovery of Scott’s work. Not only did he introduce Scott’s novels to France, but his translations, rather than the originals, were used as the source text for translations into many other languages, such as Italian, Polish, Russian, and Spanish.

With French being the common language of Europe’s educated classes, many people also read Defauconpret’s French version long before translations of Scott appeared in their own languages.

|

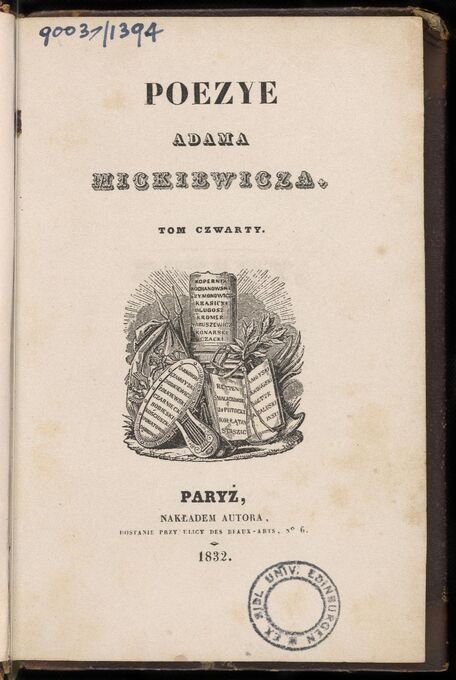

The Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz imitated Scott in the long narrative poems Grażyna (1823), Konrad Wallenrod (1828), and Pan Tadeusz (1834), which patriotically celebrate his nation’s independent past. His works served as an inspiration for uprisings against the three imperial powers that had divided the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth between them.

Mickiewicz was imprisoned in the 1820s for belonging to a nationalist secret society, and thereafter went into political exile in Paris, where this volume of his poems was published.

Other politically active Romantic nationalists who emulated Scott include Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz in Poland, Miklós Jósika, József Eötvös, and Mór Jókai in Hungary, and Václav Kliment Klicpera and Josef Kajetan Tyl in Bohemia (today’s Czech Republic).

|

In Italy, followers of Scott created fiction and poetry that were part of the Risorgimento campaign to unify the Italian peninsula as an independent nation-state. Writers like Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi, Massimo d’Azeglio, Tommaso Grossi, and Cesare Cantú wrote historically set works condemning foreign domination of Italy and aiming to reawaken national feeling. Many of these writers were imprisoned for their literary and political activities.

Scott’s novels were also frequently adapted as operas, including Gaetano Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor (1835), based on The Bride of Lammermoor.

|

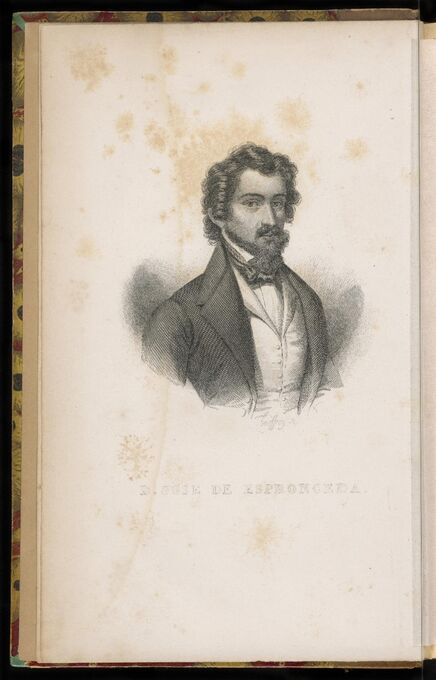

Spanish writer José de Espronceda was imprisoned for forming a secret society opposing the absolute rule of Ferdinand VII. He subsequently fled Spain in 1826, living in London then Paris, where he participated in the July Revolution of 1830. Following Ferdinand VII’s death in 1833, he was permitted to return to Spain, where he helped found the Republican Party and suffered further imprisonment for his political activities. His Scott-influenced historical novel Sancho Saldaña (1834), was written in prison in Badajoz.

Other prominent, Scott-inspired Liberal exiles include another Spaniard Joaquín Telesforo de Trueba, who turned to English to write historical novels like The Castilian (1829), and the Portuguese writers Almeida Garrett and Alexandre Herculano.

|