In the summer of 1615, Esther Inglis and her family returned to Edinburgh. That autumn, her eldest son Samuel enrolled in the Tounis College, now the University of Edinburgh. Read on to learn more about Samuel Kello’s own life and career.

A mother’s hands

Esther Inglis lived at a time when most women lacked opportunities for professional work or even an education which was comparable to that available to men. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, educated women would usually only have been part of upper or aristocratic classes. Women from lower social orders would typically enter domestic service in their teens in preparation for later managing their own household economy as a wife. Esther Inglis’ role as a wife and mother is integrated into her work as both scribe and artist.

As a middle-class woman, even one so well-educated, Inglis would also have been responsible for the running of her household. She must have balanced the production of her manuscripts with her domestic role, especially when Bartilmo Kello travelled on his governmental duties. Producing her manuscripts from home, Esther Inglis’ calligraphy and artistry can be understood as a kind of cottage industry. The money that Inglis hoped to gain by presenting her manuscripts was intended to support the growing family which surrounded her. As this section shows, Esther Inglis was making her manuscripts amongst times of joy and grief, financial strain, and concern for her children’s future.

Recent archival research has made it possible to trace the families of Esther Inglis and Bartilmo Kello across six generations, as this family tree shows. Esther Inglis was one of five children and was the mother to eight children herself, although not all survived to adulthood. Esther Inglis would also have known one granddaughter, Esther Crighton, within her lifetime. Bartilmo Kello also had a complicated childhood; he was orphaned from an early age and raised instead by two guardians including his uncle, Duncan Nairne.

|

Joining the hands of husband and wife

Having spent the first years of their married life in Edinburgh, Esther Inglis and Bartilmo Kello moved southwards to London with the family in 1604 after the accession of James VI to the English throne. This manuscript is the earliest record of their family’s stay in England. It is an album amicorum, or friendship album, belonging to a Scottish scholar called George Craig. Bartilmo Kello wrote an entry on the left, while Esther Inglis inscribed the right with quotations from the Bible. Although Bartilmo Kello shows his ability to write in a neat and stylish italic hand, he is no match for his wife; Inglis writes in five separate, perfectly clear scripts within the space of this single page.

|

||||||

| Object reference | Edinburgh University Library, MS La.III.525, folios 7v-8r |

|---|

Bartilmo Kello’s parish church

By 1608, Esther Inglis and her family had settled in the parish of Willingale Spain in Essex. Helped by Sir David Murray, Bartilmo Kello became the rector (minister) of Willingale Spain; he held this position until November 1614, when he was succeeded by Dr Edward Boosie. Kello would have preached in St Andrews church, shown here. The interior of this church is simple and whitewashed, in-keeping with its historically Puritan associations.

Today, the stone floor of St Andrews church still preserves two epitaphs for Joseph Kello and Isaac Kello, Esther Inglis’ sons who both died in 1614. Listen to these two epitaphs below.

|

Poems for her children

Esther’s sons Joseph and Isaac Kello died aged thirteen and nine respectively, probably from ‘ague’ or malaria. The epitaphs which survive on their memorials bear much similarity to Esther Inglis’ other short poems, suggesting they were written by their own mother. These verses are poignant and simple, written with care and clarity.

|

The poems for Joseph and Isaac Kello are read here by Gerda Stevenson. Click the box to read along with a transcription.

|

Leaving home

Measuring just 5 by 3 centimetres, this is Esther Inglis’ smallest known manuscript. It contains a hand-written copy of a book by John Taylor, first printed in 1614. Taylor's work contains verse summaries of the Old and New Testaments. This manuscript was a gift to Samuel Kello as he left home to attend university in Edinburgh. Esther dedicated the manuscript to her “well-loved sonne” and composed a dedicatory verse for Samuel at the start of this book.

Click here to see a full digitisation of this manuscript.

|

||||||

| Object reference | Houghton Library, Harvard, MS Typ 49, folio 2r | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit / Usage information | Houghton Library, Harvard University |

Listen to Esther Inglis’ verse for her son Samuel, read by Gerda Stevenson. Click the box for a transcription.

|

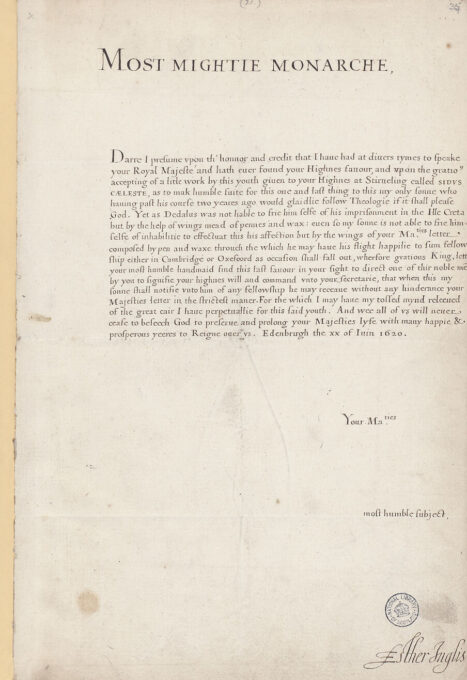

An appeal to the King

Esther Inglis was not afraid to use her connections at the royal court to ensure her family’s livelihood. In 1620, she wrote this letter to King James, asking him to find a fellowship for Samuel at the universities of Oxford or Cambridge. In her letter, she expressed her concern for Samuel’s wellbeing [“the great cair I have perpetuallie”], anxious that her son should have a comfortable life and a safe future. The letter makes it clear that she knew the King of Scotland and England personally, and that he was likewise aware of her family’s situation.

|

||||||

| Object reference | National Library of Scotland, Adv. MS 33.1.6, Vol. 20, no. 21 |

|---|

Beyond securing a future for Esther Inglis’ son, King James VI/I certainly assisted in other aspects of her family’s life. In 1621, James secured a new position for Bartilmo Kello as rector of the parish of Spexhall in Suffolk, England. Strangely, Bartilmo did not keep this post for long ; just eight months later he was replaced by his son, Samuel. Samuel Kello himself would remain as the rector of Spexhall for the next sixty years.

The end of the scribal line?

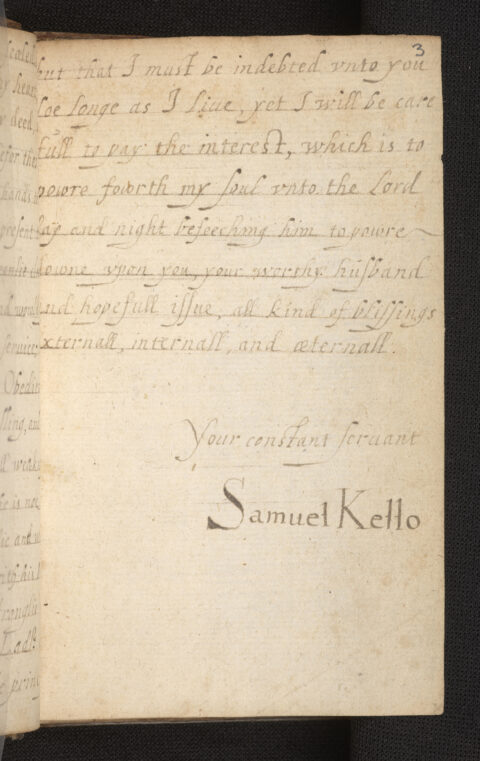

Esther Inglis was taught calligraphy by her own mother, and it might be expected that she would have guided her own children’s handwriting. Samuel Kello’s own writing, however, does not show much of his mother’s influence.

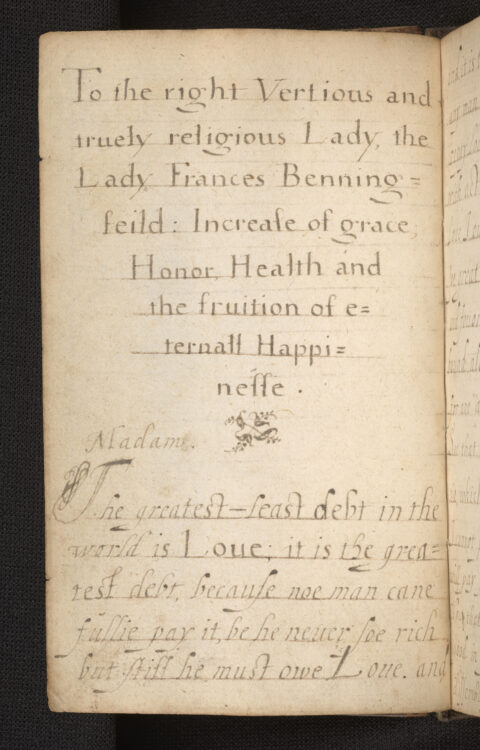

Samuel Kello wrote this manuscript while living as the rector of Spexhall. It is a treatise of spiritual guidance dedicated to Lady Frances Benningfield (1595-1630), a neighbour of Samuel’s who shared his Protestant faith. This manuscript may be a draft copy of a gift for Lady Benningfield. Although Samuel does attempt to imitate parts of a printed book by hand, and includes some calligraphic decoration, his work does not quite match the standards set by Esther Inglis herself.

Click the images below to see close-up examples of Samuel’s handwriting.

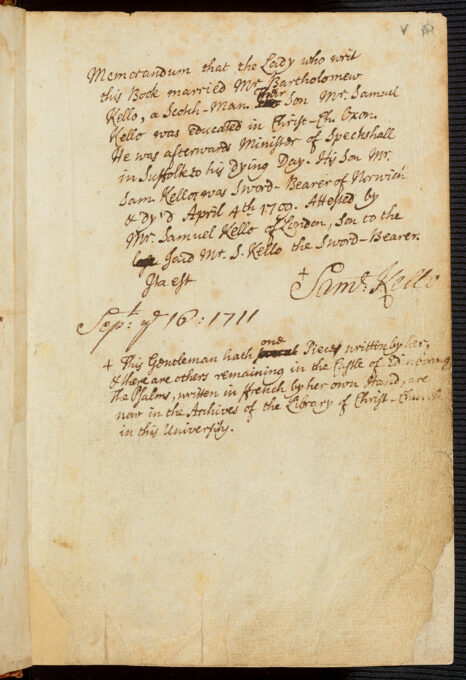

Remembered through generations

On the 16th September 1711, a different Samuel Kello sat in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. He wrote a note in this calligraphic manuscript of Proverbs, written by his great-grandmother, Esther Inglis, over a century earlier. This Samuel Kello, grandson to the minister of Spexhall, states that his grandfather had attended Christ Church at the University of Oxford. This is the only known suggestion that Esther Inglis’ request to King James in 1620 may have been successful.

Samuel Kello also states that he now owns one book by Esther Inglis himself -- it is likely that this is the miniature manuscript made by Inglis in 1615, now passed down through three generations.

Click here to see Esther Inglis’ manuscript in full.

|

This note written by Esther Inglis’ great-grandson offers just one example of how Inglis and her manuscripts have been remembered and celebrated in the centuries following their creation. The final section of this exhibition takes this further, bringing together 400 years of readers, scholars, and artists all responding to Esther Inglis’ manuscripts into their own ways. Read on to discover more.