Afterwords

Esther Inglis, 1624-2024

Since her death on 30th August 1624, Esther Inglis has been celebrated as a remarkable writer and an exceptional woman. Seventeenth-century testimonies survive from friends and writers who saw Inglis’ manuscripts, and scholars and antiquaries continued to praise her in the eighteenth century. In 1865, the Scottish bibliographer, antiquarian and editor David Laing (1793-1878) published a landmark account of the manuscripts by Inglis which he had seen or collected. Laing bequeathed his own manuscript collection to the University of Edinburgh, which included five manuscripts by Esther Inglis, and one associated with her circle. However, beyond academic scholarship and until very recently, Esther Inglis’ work has been largely forgotten within narratives of Scottish cultural history.

This final section brings together a range of responses to Esther Inglis’ life and work which span the four hundred years since her death, showing how Esther Inglis’ manuscripts have continued to influence writers, artists, and makers.

“Patterns and examples... to all the men and women”

Esther Inglis’ exceptional skills in calligraphy were known and praised by other scribes within her lifetime. In 1638, a Scottish professional scribe named David Browne published a book on the theory of writing, The Introduction to the True Understanding of the Whole Arte of Expedition in Teaching to Write. In this book, Browne lists the names of other scribes and writers who he knows in Scotland, with Esther Inglis among them. He describes Esther Inglis’ intricate calligraphy as offering its viewers “patterns and examples, as well for practice as teaching" which they can try to copy themselves.

|

In this extract, David Browne says that he had previously asked Inglis (who he calls “Esther English”) to compete against him in a handwriting contest, but that she had refused this invitation.

Click the box to read this extract of Browne’s text.

|

Early additions to library shelves

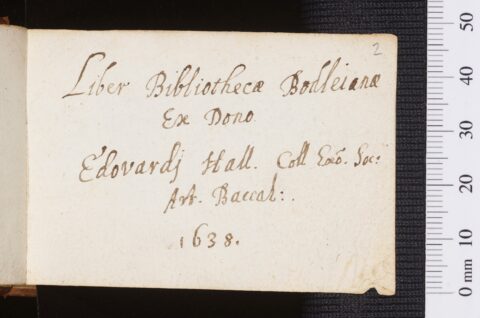

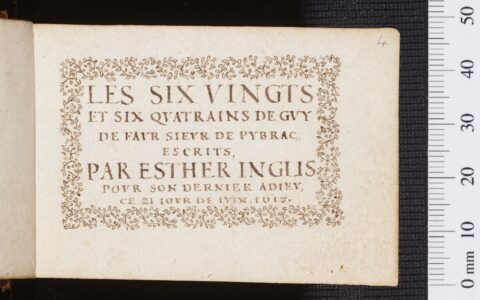

Esther Inglis’ manuscripts have taken very different paths since their first creation. Some manuscripts have remained in the hands of the families for which they were made, while others quickly found their way into royal or national libraries. This small manuscript was made by Esther Inglis in 1617 for Joseph Hall, the bishop of Norwich, and Hall passed this manuscript to his son Edward. In 1638, Edward Hall donated it to the Bodleian Library, which had opened at the University of Oxford in 1602.

Click here to see a full digitisation of this manuscript.

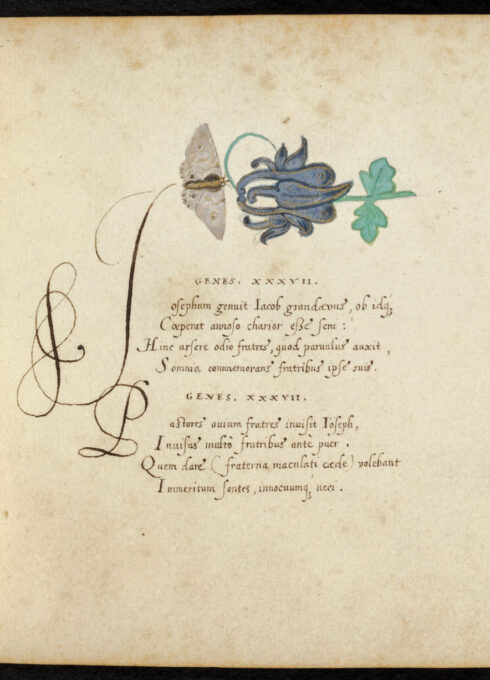

Collage and re-use

Not all of Esther Inglis’ manuscripts have been treated with the same care in the centuries since their creation. This manuscript was originally one of Inglis’ floral, illuminated books; now it is fragmented, with nearly all its flowers having been cut out. Although the motivation for this fragmentation is unclear, it is likely that a later reader wanted to gather these individual botanical paintings for their own collection or collage.

See the full manuscript here.

|

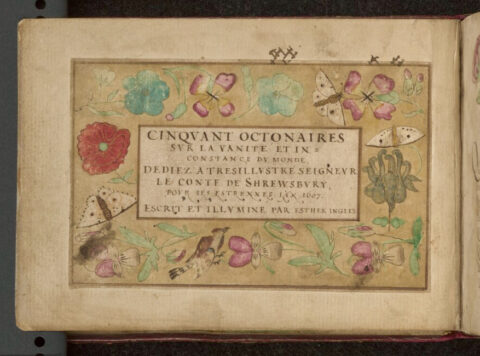

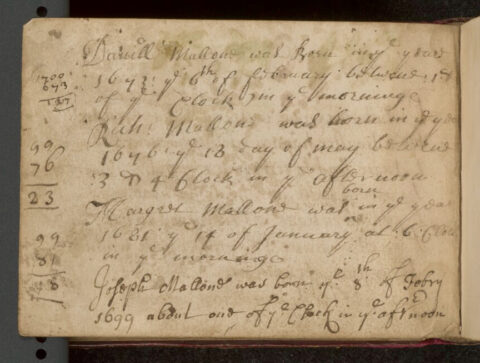

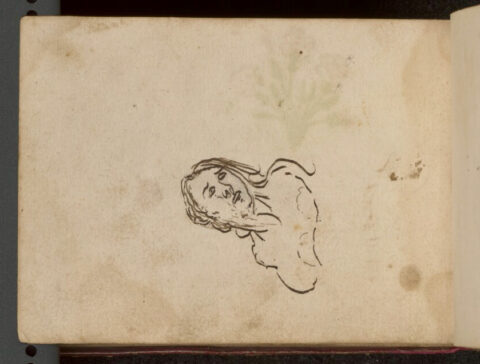

From devotional manuscript to family album

Although Esther Inglis originally produced this illuminated manuscript for Gilbert Talbot, the 7th Earl of Shrewsbury, it had transferred to the Mallone family by the later seventeenth century. In their hands, Esther Inglis’ manuscript was turned into a kind of family album. Pages originally left blank by Esther Inglis now record the birth dates and times of the Mallone children (David, Richard, Margaret and Joseph), between 1673 and 1699. Doodles and drawings have been added to other blank pages in this manuscript, as it continued to pass from one owner to another.

View a full digitisation of this manuscript here.

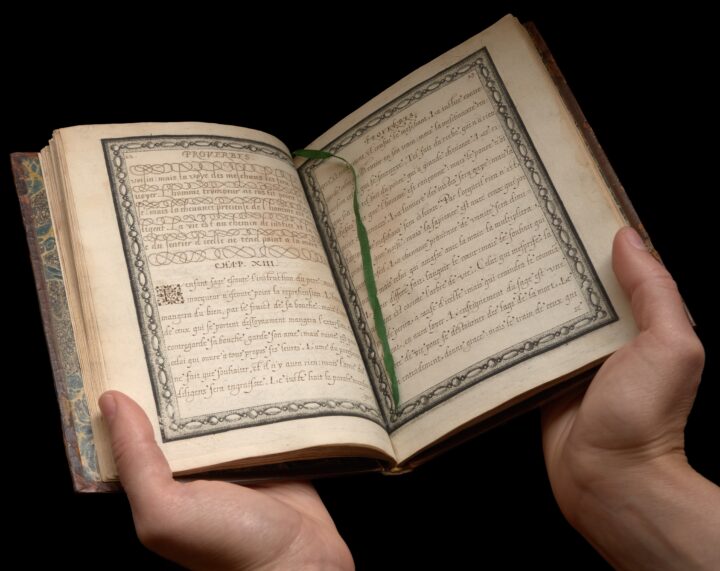

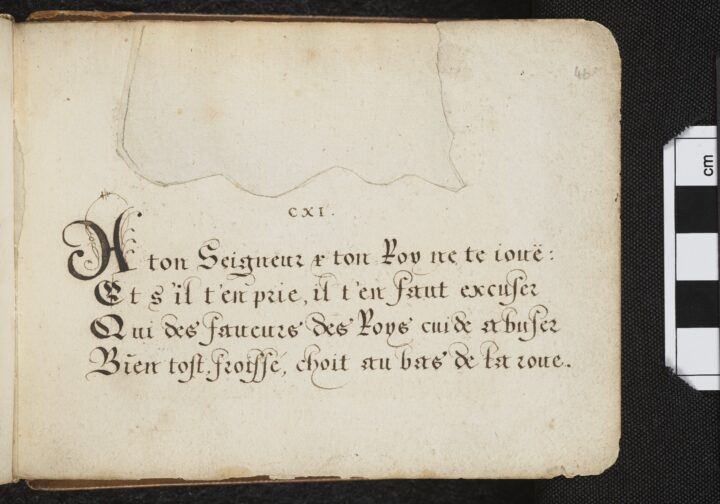

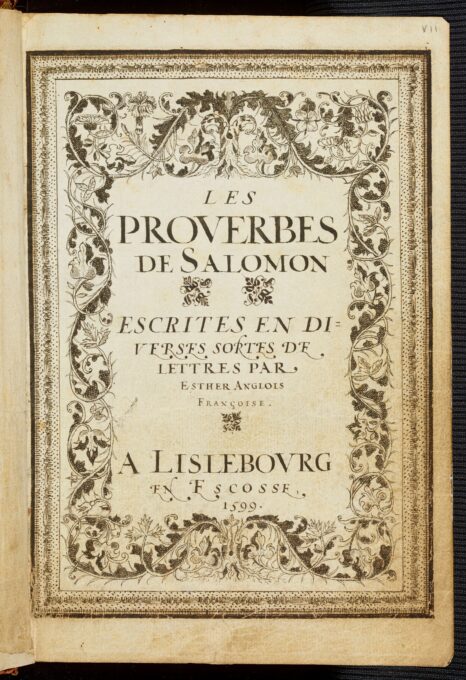

“Among the nicer curiosities"

On the 11th July 1654, the English diarist and writer John Evelyn described a visit to the Bodleian Library, where the librarian Thomas Barlow had chosen a particular range of its treasures to show him. Among these were the intricate Proverbes de Salomon which Esther Inglis had written for Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, in 1599. The manuscript had been given to the Bodleian in 1620 by Sir Thomas Neville. Click the box to read Evelyn’s description of this manuscript, which he describes as “among the nicer curiosities” of the Bodleian Library.

|

Collecting a “celebrated Calligraphist"

The Scottish bibliographer and historian David Laing was the first to compile a catalogue of Esther Inglis’ work, which he titled “Notes relating to Mrs Esther (Langlois or) Inglis, the celebrated Calligraphist”. Laing himself owned six pieces of writing by Inglis, which he bequeathed to the University of Edinburgh on his death. This manuscript is inscribed with Laing’s signature from 1867, and the note “This book appears to be in the handwriting of Esther Inglis”. The manuscript is the treatise on British union written by David Hume, copied out by Esther Inglis and intended as a gift for King James VI/I.

View this manuscript in full here.

|

||||||

| Object reference | Edinburgh University Library, MS La.III.249, inner front board |

|---|

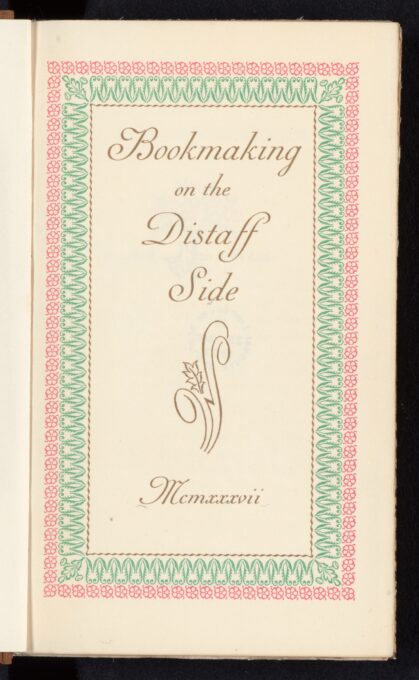

Esther Inglis among the book-makers

Bookmaking on the Distaff Side is a unique collection of writings which celebrate the roles of women in the history of bookmaking and printing. It was printed independently by a women’s publishing house in 1937 and contains one of the earliest studies of Esther Inglis’ life and manuscripts, written by Dorothy Judd Jackson. Jackson’s study of Esther Inglis’ calligraphy is set alongside stories of women as printmakers, illustrators, and typesetters, from the words of Gertrude Stein to the art of Wanda Gág. Jackson also published a new catalogue of Esther Inglis’ manuscripts, which records 41 works by Inglis compared to the 28 first described by David Laing in 1865. These endeavours to bring Esther Inglis’ manuscripts together meant that the range and scale of her work could begin to be appreciated.

|

Manuscripts to tea-cups

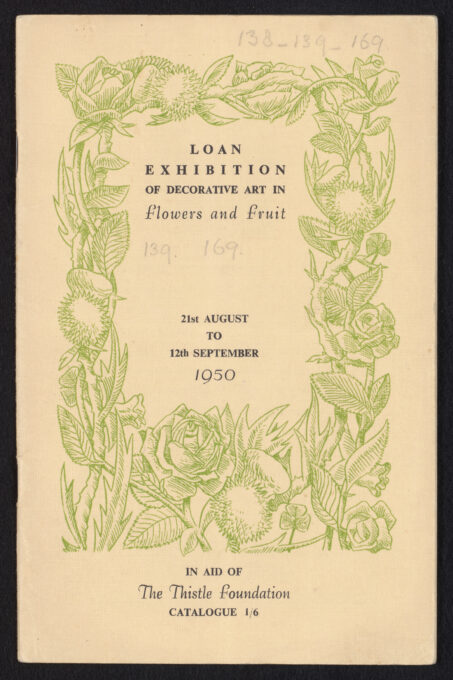

Esther Inglis’ manuscripts have delighted their audiences for many different reasons over the centuries since their creation, whether for their craftsmanship, their size, their scripts, or their illuminations. Until the late twentieth century, however, the view of her manuscripts as ‘decorative’ objects limited the scholarly study of her work.

In 1950, Edinburgh’s Thistle Foundation chose one of Inglis’ manuscripts to be included in their exhibition on “Decorative Art in Flowers and Fruit”. The manuscript was Inglis' 1607 paraphrase of St Matthew’s Gospel, now in the National Library of Scotland. Esther Inglis’ illuminated book was exhibited alongside botanical paintings, jewellery shaped like fruits or flowers, and even painted teacups.

|

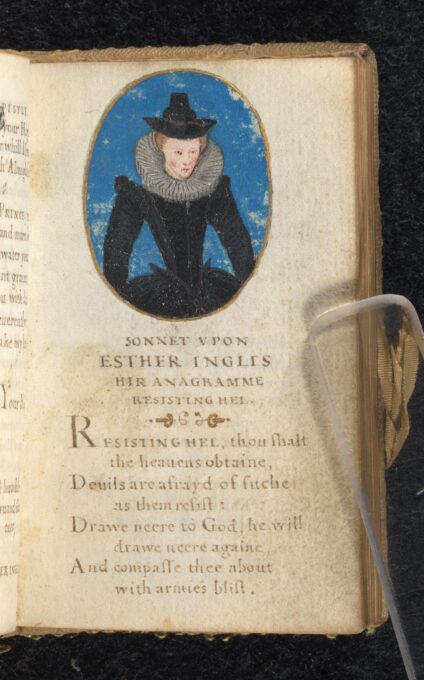

Updating the anagram

Two of Esther Inglis’ manuscripts include a sonnet by the Scottish poet George Douglas which is based on an anagram of her name, RESISTING HEL. In 2013, the poet David Kinloch wrote an acrostic poem for Esther Inglis structured by this same anagram. Kinloch’s poem combines many images, words and scripts found within Esther Inglis’ manuscripts, from her painted flowers to the designs she draws in pen.

Click the box below to read David Kinloch’s poem, “Resisting Hel".

|

Poetry in fragments

Gerda Stevenson’s poetry collection QUINES includes her Nine Haiku for Esther Inglis. Each Haiku contains a fragment of Inglis’s work as scribe, artist, and woman. The haiku structure is drawn from Japanese poetry, and Stevenson uses this form to gesture towards deeper narratives in Esther Inglis’ creative practice.

Listen to Gerda Stevenson reading her Nine Haiku here and click the box to read along with her poem.

|

|

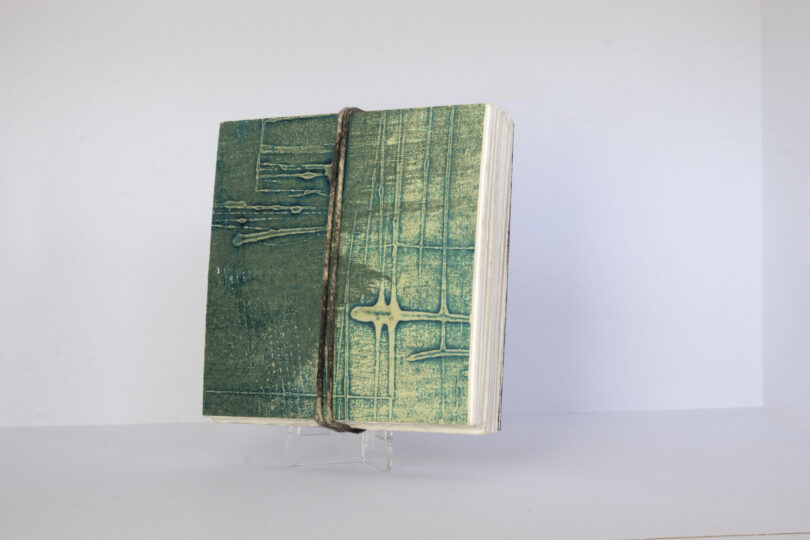

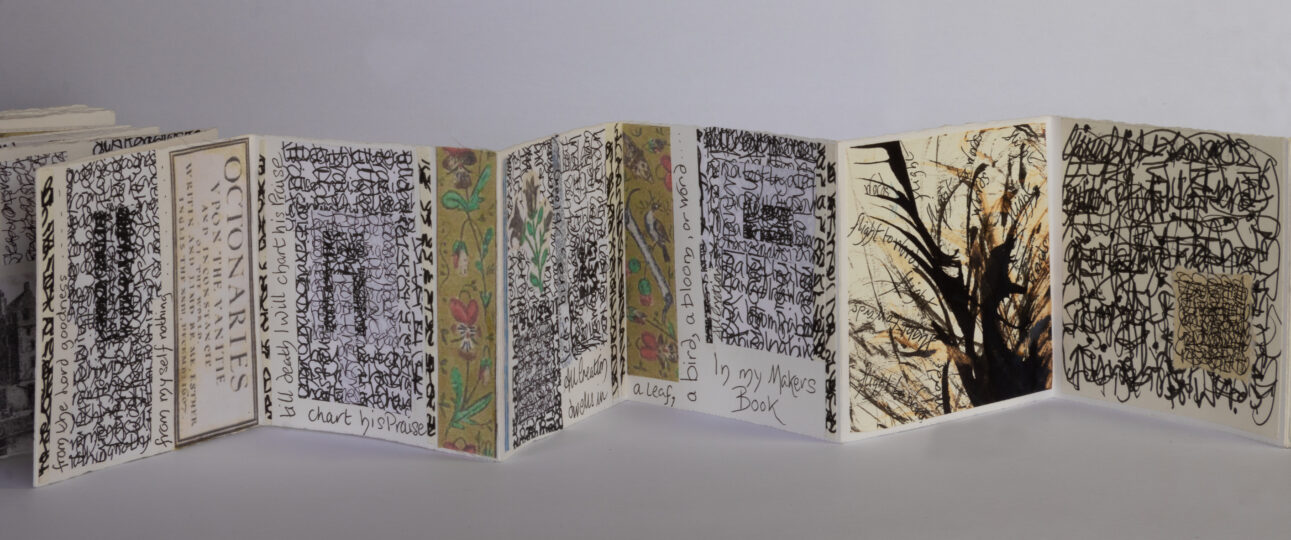

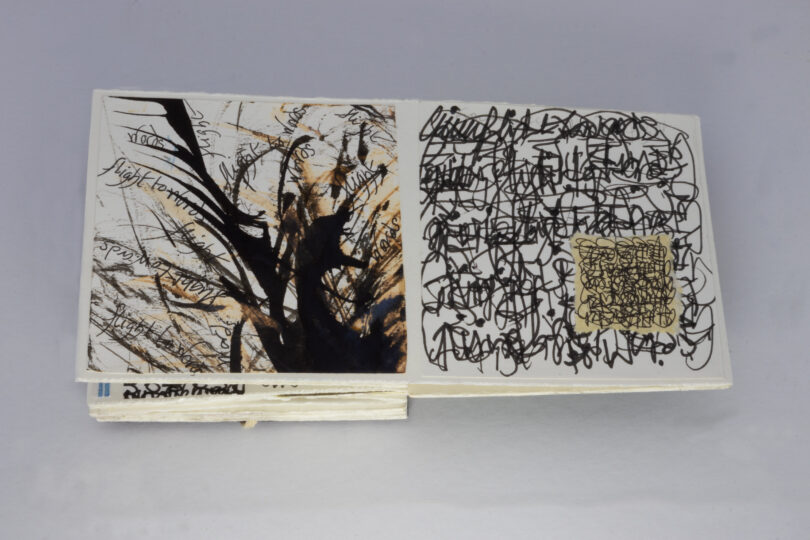

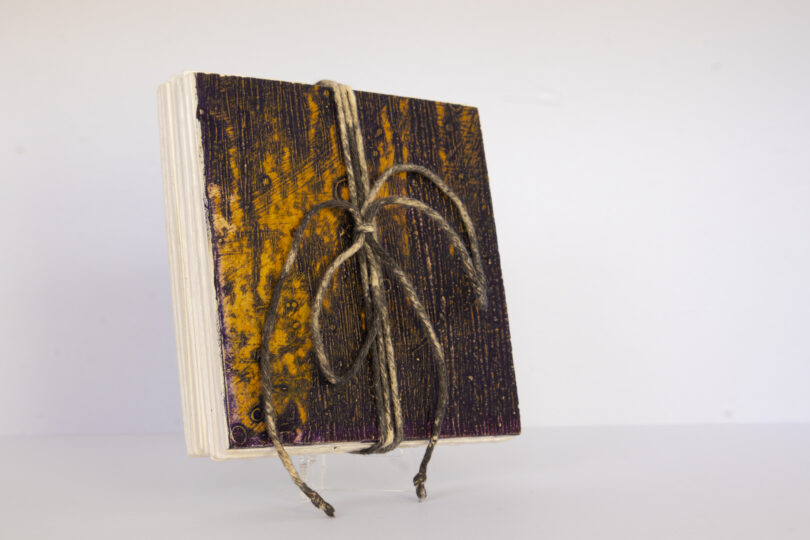

This artist’s book was produced by Helen Hill as part of the QUINES exhibition by Edge Textile Artists Scotland, for which each artist worked from a different piece in Gerda Stevenson’s poetry collection. The book has a concertina form, its textured exterior revealing pages covered in expressive, calligraphic marks which are set against fragmented images of Esther Inglis’ own manuscripts.

Hill says, “Haiku poetry is a perfect vehicle for telling Esther’s tale. Whilst it has a seeming simplicity, it often contains contrasts, opposites, the unusual and the unexpected. ... I concentrated on calligraphy – not Esther’s own, but making patterns of my own calligraphic interpretation. I wrote single words and phrases from Gerda’s poem over and over again in different directions and overlaying text to make it almost indecipherable. But the words were there.”

|

||||||

| Credit / Usage information | Calum Campbell |

|---|

|

||||||

| Credit / Usage information | Calum Campbell |

|---|

|

||||||

| Credit / Usage information | Calum Campbell |

|---|

|

||||||

| Credit / Usage information | Calum Campbell |

|---|

|

|