Esther Inglis has so far been introduced as a scribe and an artist who works with pen, brush, and needle -- but there was still more to her creative practice. The next section of this exhibition focuses on Esther Inglis as an author, exploring the literary texts which Inglis wrote herself. Read on to discover more.

Self-portraits of the artist

Over twenty-five of Esther Inglis’ known manuscripts contain self-portraits -- the earliest examples produced by a woman in Scotland or England. These portraits allowed Inglis to control the image of herself as the author of her work and as a Huguenot woman. Her portraits show the influence of early-modern engravings and sixteenth-century paintings.

Inglis often presents herself in the act of writing, reminding viewers that her own hands have made every mark they see in the pages of her manuscripts. Scroll down to discover the four styles of self-portrait which Esther Inglis developed across her life, introduced with audio by Dr Georgianna Ziegler.

Portraits in pen, 1599-1602

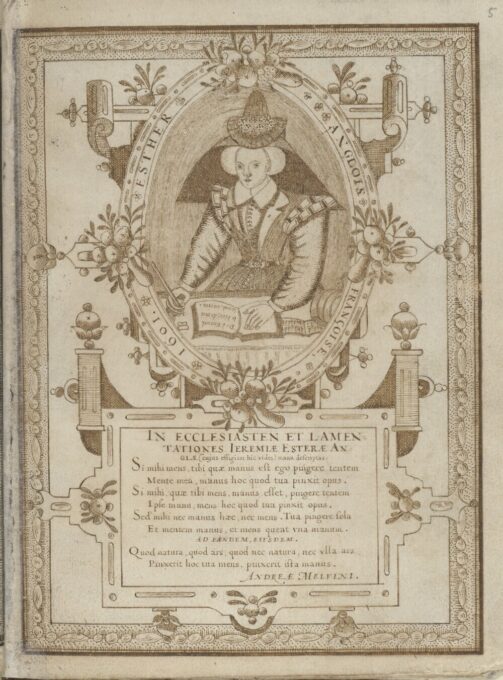

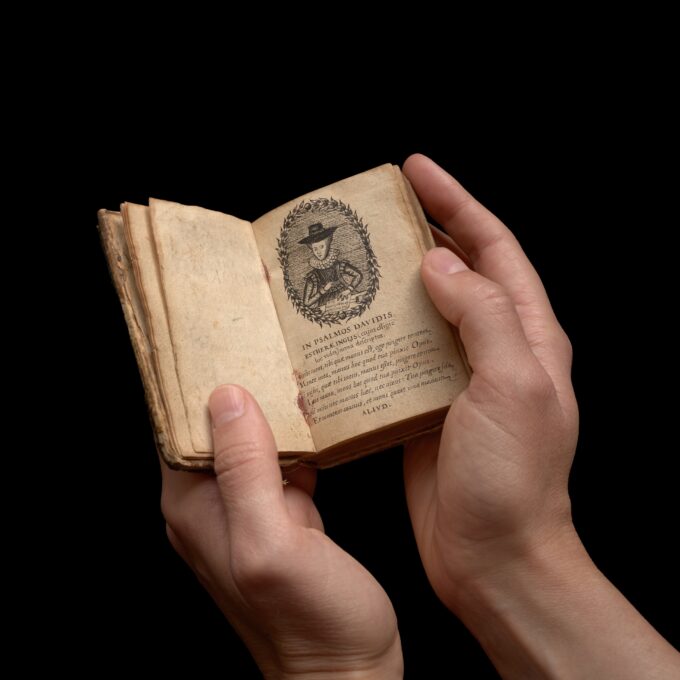

Between 1599 and 1602, Esther Inglis drew her self-portraits in the style of printed engravings, using techniques including cross-hatching to imitate printed lines of ink. She surrounded her portraits with ornamental, architectural frames and added classical imagery in a style typical of Renaissance art. However, the design of these portraits is not her own; she worked from an engraved portrait of a Huguenot poet, Georgette de Montenay (1540-1581). Listen to Georgianna Ziegler describing these portraits below.

|

|

This engraving of the French Huguenot poet, Georgette de Montenay, was designed and engraved by Pierre Woeiriot (1532-1599). It was included at the start of Montenay’s book of Christian emblems, Emblemes ou Devises Chrestiennes (1567). The motto which Montenay writes is “O plume en la main non vaine” [A feather in the hand is not in vain]. Following Pierre Woeiriot’s model, Esther Inglis also included verses about her beneath her portraits. The verse shown in this portrait of Georgette de Montenay is based on a French anagram of her name, “Gage d’or tot ne te meine” [Let not the promise of gold guide you].

Follow the arrows in the image below to view one of Esther Inglis’ early self-portraits in greater detail, showing how she responds to this image of Montenay.

|

|

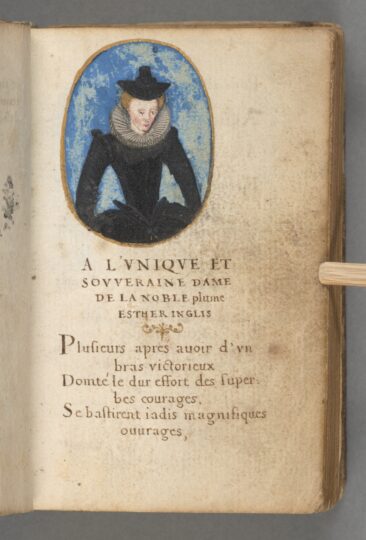

Portraits in full colour, 1606-1612

When Esther Inglis begins producing her illuminated manuscripts, around the year 1600, her style of self-portrait also changes. These portraits retain the image of Inglis writing at a desk, but she now works in colour and takes fewer elements from the original portrait of Georgette de Montenay. By painting a colourful image of herself writing into her books, Inglis presents herself confidently as both a scribe and an artist. Listen to Georgianna Ziegler introducing these portraits in more detail, and click the box to read along with a transcription.

|

||||||

| Object reference | Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Ms. lat. oct. 14, folio 2v | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit / Usage information | Public Domain Mark 1.0 |

|

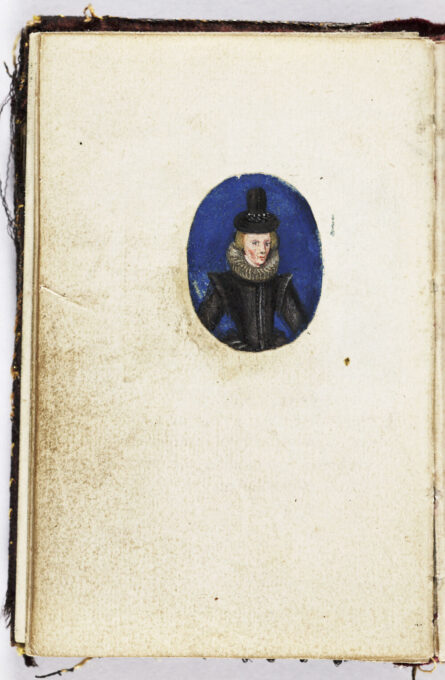

Esther Inglis’ coloured portraits closely follow the style of Renaissance painted miniatures produced by artists like Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619) and Isaac Oliver (c.1565-1617). These miniature portraits usually include a round or oval frame and a vivid blue background and were very fashionable in sixteenth-century England. Inglis and her family moved from Edinburgh to London in 1604, and it is likely that Esther Inglis became familiar with these limned portraits while in England. Click the arrows to compare Esther Inglis’ self-portraits to other Renaissance portrait miniatures.

|

This portrait by Nicholas Hilliard depicts an English woman of an upper class, with her status shown by her lace collar, smocked dress, and decorated hat. Hilliard has painted his sitter with the same three-quarters profile as Esther Inglis adopts in her own self-portraits, and the woman is painted against the rich blue background which is typical of the Renaissance portrait miniature.

|

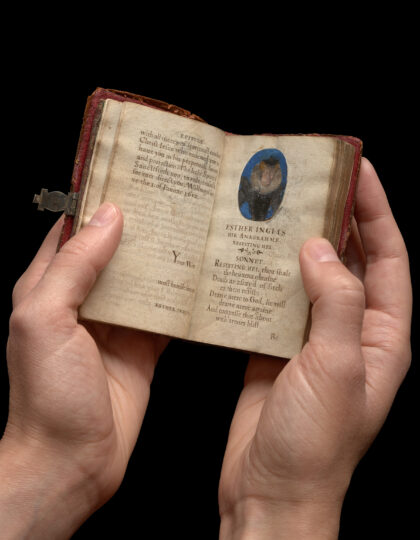

Esther Inglis clearly references Hilliard’s portrait miniatures in her own manuscripts of 1612-1615, replicating the blue background and golden oval frame. This self-portrait is included in a small book of Psalms which she produced for Henry, Prince of Wales, and is here accompanied by the opening to a sonnet praise of Inglis attributed to the Scottish poet George Douglas.

|

This portrait by Nicholas Hilliard is thought to depict Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, favourite of Queen Elizabeth I and a prominent English nobleman. Esther Inglis herself also dedicated a beautiful manuscript of the Proverbs to Essex in 1599.

|

Between 1612 and 1615, Esther Inglis’ self-portraits responded even more closely to the miniatures of artists like Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver. During these years, Inglis painted her blue, oval portraits onto small individual pieces of paper which were then cut out and pasted into her manuscripts. This replicates the process of portrait artists whose miniatures would have been painted onto oval pieces of parchment and then fitted into a frame.

Copy, paint, paste: Esther Inglis’ third portrait type

Esther Inglis’ third type of self-portrait is found in five manuscripts which date from 1612 to 1617. These are also in colour; Esther Inglis painted these portraits onto small ovals of card before pasting them into her manuscripts. These portraits bear close resemblance to her second type, except for her hat which is now taller, reflecting another change in English fashions at this time.

|

||||||

| Object reference | National Library of Scotland, MS 8874, folio 4v | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit / Usage information | National Library of Scotland |

Esther Inglis’ later portraits: drawing on her past

In the later years of her life, Esther Inglis returned to her earliest self-portraits as a model. The self-portraits she drew in 1624 once again use the engraving of Georgette de Montenay as their model, although often without the addition of the lute and music book. In these later portraits, Esther Inglis depicts herself in the same posture as Montenay, holding a pen suspended over the page before her. The small book on her desk may also reference the miniature manuscripts which Inglis was making in the final years of her life.

Listen to Georgianna Ziegler describe these later self-portraits and click the box to read along with a transcription.

|

|

|

||||||

| Object reference | Folger Shakespeare Library, V.a.91, folios 1v-2r |

|---|

A possible engagement or marriage portrait

Perhaps the most widely-known image of Esther Inglis, this portrait was painted when she was around 25 years old. Its artist and the reason for its commission are still unknown, but its date suggests that it was occasioned by Inglis’ engagement to Bartilmo Kello, who she married around 1596. Listen below to Georgianna Ziegler introducing this portrait and Esther Inglis’ fashion, and click the box to read along with a transcription.

|

|

This modern reinterpretation of Esther Inglis’ 1595 portrait was made by the ceramicist Karin Hessenberg, as part of a trio of sculptures depicting middle-class Protestant women in early-modern England and Scotland. In the original trio, Esther Inglis is set alongside the figures of Joan Alleyn and Joan Popley, whose early-modern portraits are very similar to Esther. Inglis’ own. Each woman wears a tall black hat, a black dress and a white ruff, and each holds a small, bound red book. Esther Inglis' painted portrait presents her as a woman of her own time, closely conforming to societal expectations. This portrait contrasts with the agency and creativity which Esther Inglis expresses in the self-portraiture found within her own manuscripts.

|