The scripts and the words of Esther Inglis’ manuscripts are only part of their intrigue. Inglis’ books are also intricately decorated with pen-work drawings, and carefully bound in a variety of styles. Read on to learn about Esther Inglis’ work as an early-modern artist.

Reasons for writing

Esther Inglis knew that her skills would delight and captivate her audiences, and she chose her recipients carefully. Like others who gave gifts in early-modern Scotland and England, Inglis hoped that her recipients would offer money in reward for her exceptional skills, and that these individuals might become her lasting patrons. Records show that Inglis did receive patronage for her work, but financial circumstances remained tight for Esther Inglis and her husband, Bartilmo Kello, throughout their marriage.

But monetary gain was not Esther Inglis’ only motivation for producing her manuscripts. By gifting her manuscripts books, she was able to establish alliances with different individuals, assert her support of political or religious causes, or encourage her recipients to take specific actions. Esther Inglis often dedicated her manuscripts to others who shared her Calvinist faith, and she used her books to demonstrate the depth of her religious belief. Through her gifts, Esther Inglis hoped to be remembered by her recipients and to become known within particular circles.

Writing in hope of reward

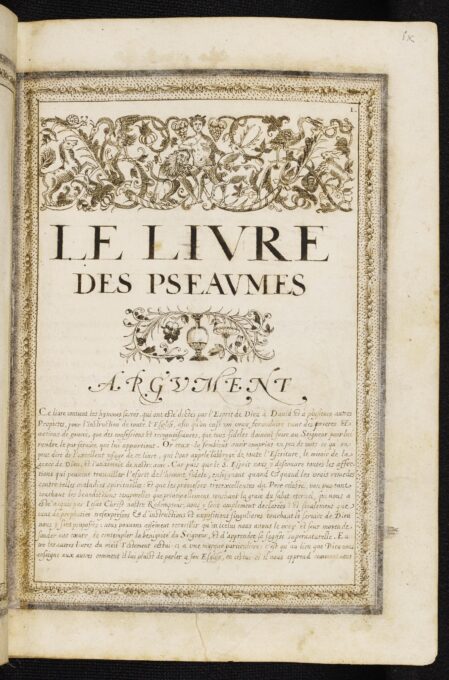

In the summer of 1599, Esther Inglis’ husband Bartilmo Kello travelled from Edinburgh to London to deliver this calligraphic Book of Psalms to Queen Elizabeth I. Although it would be an honour to offer a such a book to the Queen, both Kello and his wife were also expecting some monetary reward for this gift. Kello wrote a series of letters on this journey which describe him waiting anxiously in London for repayment from the Queen before he could return to Edinburgh.

See the full digitisation of this manuscript here.

Listen to extracts from these letters in the audio clips below, read by Jamie Reid Baxter.

|

This letter was written by Bartilmo Kello to Anthony Bacon at London, dated the 14th July 1599. In this letter, Kello explains that he had been waiting to hear back from a “Mr Sackforde”, a groom of the Privy Chamber, to whom he had delivered the Book of Psalms by Esther Inglis. At the time of writing this letter, Kello was still waiting for repayment from the royal household. He was becoming anxious about the amount of money that he was wasting as he continued to wait in London.

|

Four days later, on the 18th of July 1599, Bartilmo Kello was still waiting for his reward for the Book of Psalms which Esther Inglis had made for Elizabeth I. Kello decided to write to the Queen herself. Trying not to ask for money directly, Kello instead described his difficult situation in this letter, explaining that he had no choice but to stay in London until he heard more about a reward.

|

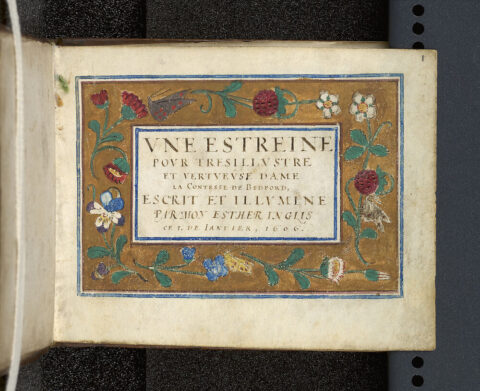

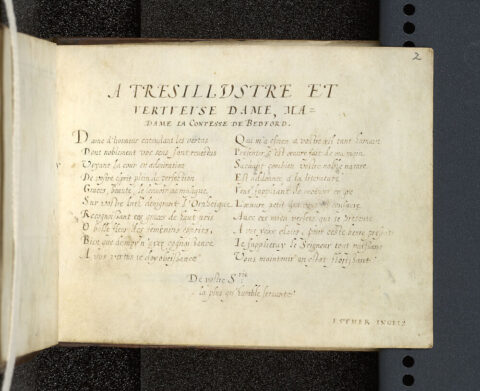

Proverbs for a well-known patron

Esther Inglis often chose to dedicate her manuscripts to individuals known for their patronage, increasing her chances of gaining financial reward. Lucy Harington, Countess of Bedford (1581-1627) was known to be a generous patron of the arts as well as a favourite of Queen Anna of Denmark, wife of James VI/I. For someone in Inglis’ position, Lucy Bedford would have been an important individual with whom to gain favour. Inglis made this manuscript of Proverbs as “une estreine”, a gift for the New Year.

See the full manuscript here.

Planning for patronage

Christian Friis (1556-1616) was a Danish nobleman, statesman, and patron, famed for his generosity. In the summer of 1606, he visited London accompanying King Christian IV, Anna of Denmark’s brother. Esther Inglis’ French dedication to Friis makes it clear that she has been waiting over five months (“il y a plus de cinq mois”) for his arrival. Inglis prepared this manuscript in Friis’ honour, hoping to gain his favour and patronage while he was in England.

Click here to see the manuscript in full.

|

||||||

| Object reference | Berlin State Library, MS. Lat. Oct. 14, folio 2r | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit / Usage information | Copyright: Berlin State Library |

A husband-wife enterprise

It was very rare for Esther Inglis to collaborate on a manuscript with anyone else, but this book was produced together with her husband Bartilmo Kello. The manuscript contains an English translation of a French treatise by Yves Rouspeauon the Calvinist doctrine of the Eucharist. Esther Inglis copied Kello’s translation in fine imitation of a printed book, The manuscript was presented to their friend Sir David Murray in 1608, thanking him for his assistance in finding Kello the rectorship of a parish in Essex.

View the full manuscript here.

|

||||||

| Object reference | Edinburgh University Library, MS La.III.75, folio 1r | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit / Usage information | University of Edinburgh, licensed under Creative Commons |

A ‘professional’ commission

Very occasionally, Esther Inglis also copied texts on behalf of others. In 1605, she produced this copy of a political treatise for its author, the poet and historian David Hume of Godscroft (1558-1629). Hume’s treatise is the second he wrote in support of closer political alliance between England and Scotland, following the union of the crowns in 1603. Hume dedicated his work to King James VI/I and Prince Henry Frederick, and the quality of Inglis’ copy suggests that he intended this manuscript as a gift to the royal household. The single flower added to the title-page signals that this unsigned manuscript is Esther Inglis’ handiwork.

Click here to see view this manuscript in full.

|

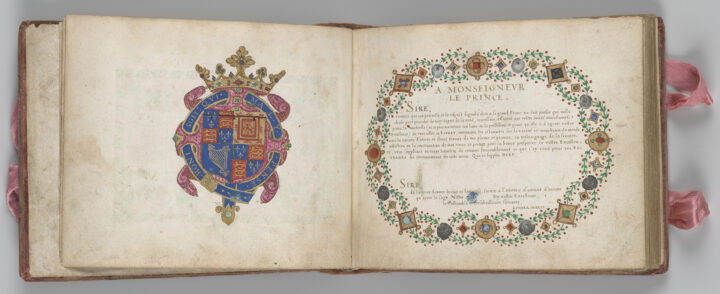

Crafting connections

Esther Inglis was able to establish connections with particular social or political networks through the gift of her manuscripts. This is one of five surviving manuscripts which Inglis presented to Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, whom she generally called ‘Prince of Britain’. Many of her other illuminated manuscripts were dedicated to figures in Prince Henry’s royal household, as she sought to gain favour within this influential network. Her introduction to the Prince's household was likely made by her friend Sir David Murray, Gentleman of the Bedchamber to Prince Henry.

|

Supporting political union?

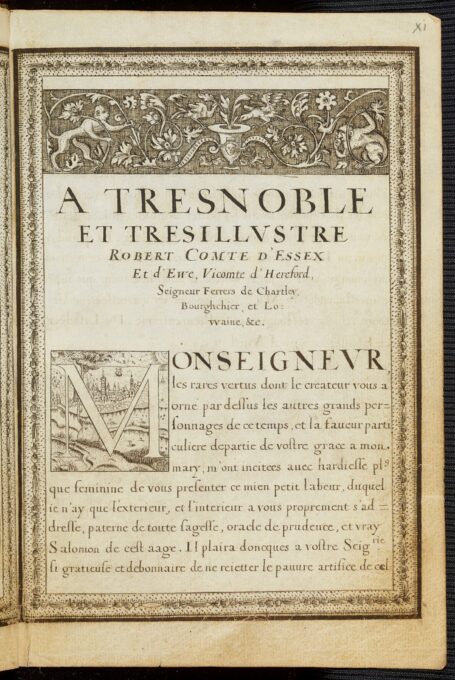

The act of gift-giving also allowed Esther Inglis to show her support of political causes. In 1599, she dedicated this decorated book of Proverbs to Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex (1565-1601). Just days later, she presented a very similar volume to Anthony Bacon, Essex’s secretary. At this time, Essex and Bacon were both strong supporters of James VI’s succession to the English throne, and Bacon was keen to promote a political alliance between Essex and James.

It is possible that Esther Inglis’ gifts show she was equally in favour of this alliance, and that the timing of these presents demonstrate her support of their political position.

See a full digitisation of this manuscript here.

|

Defending the faith through manuscript

As a devout Huguenot, Esther Inglis also used her manuscripts to demonstrate her belief in the Protestant cause. This calligraphic book of Psalms was given to Prince Maurice of Nassau, a leader in the Dutch Revolt against the Catholic Spanish Empire, and a committed Protestant. Inglis dedicated similar manuscripts to other Protestant defenders between 1599 and 1601, including Catherine de Parthenay-Larcheveque, Vicomtesse de Rohan, Catherine de Bourbon, and Henri de Rohan.

View this manuscript in full here.

|