Beginning as a student of early-modern handwriting manuals, Esther Inglis soon became a master in her own right. Esther Inglis’ manuscripts rivalled the work of the scribes who surrounded her, in the beauty of her writing and her ability to replicate printed sources by hand. As a woman working within a male-dominated world, she transformed the scripts she learned from others into emblems of her creative potential. As a Huguenot Christian, Inglis also used her handwriting as a way of doing justice to the words and works of her God. Read on to find out more.

A scribe beyond others

At a time when most women would not even have been able to write their own name, Esther Inglis grew up to master more than forty different styles of writing and received money for the manuscripts she made. She learned some scripts directly from her mother and others from the books of professional teachers of handwriting, known as “writing masters”.

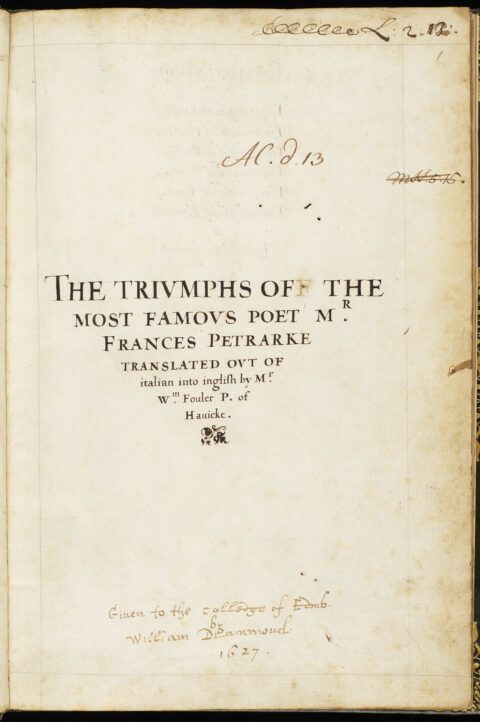

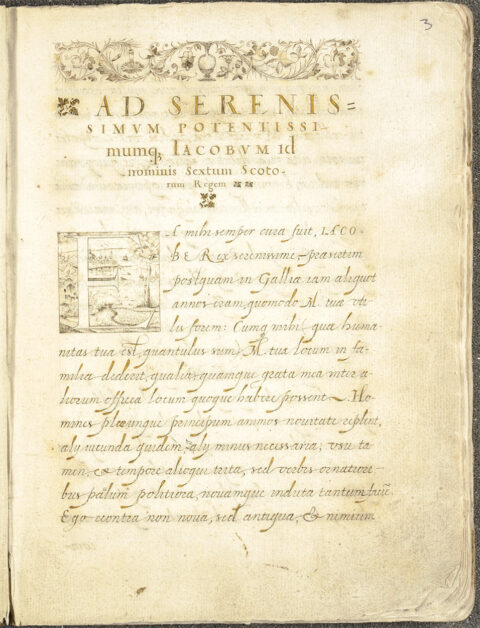

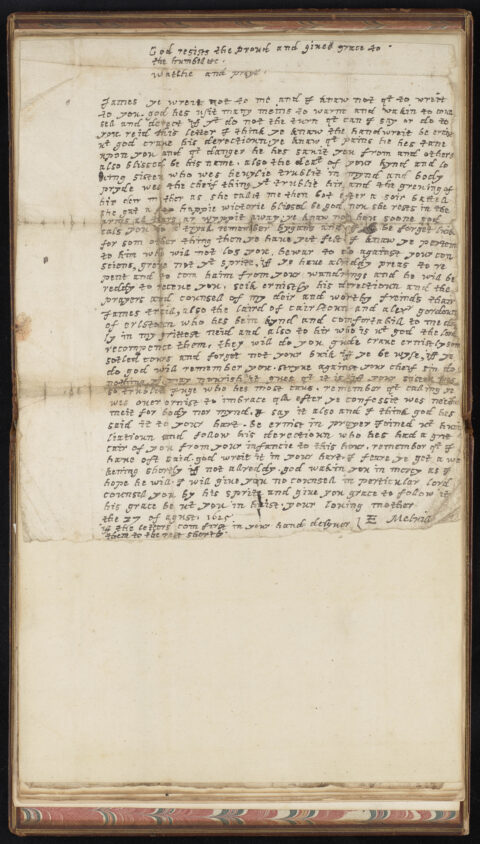

In early-modern Scotland and England the typical professions for writers might be clerks, secretaries, copyists or teachers, but Esther Inglis’ work does not fit this model. Most of Esther Inglis’ manuscripts contain copies of printed texts, including religious poetry and the words of the Bible. By rewriting and decorating these texts in new ways, Esther Inglis transformed the words of others. Rather than working to commissions, she offered her manuscripts to recipients of her own choosing, hoping to amaze them with her skills and encourage them to become her patrons. Read on to situate Esther Inglis’ manuscripts within an early-modern culture of handwriting.

Many new styles of handwriting emerged across the sixteenth century in Western Europe. In part this was a response to print technologies; the increased popularity of print had reduced the need for hand-written booksand printed books had an increasingly uniform appearance. Reacting against this, some early-modern scribes looked for deliberately new ways to shape their letters.Such scribes were known as ‘writing masters’; although the word calligraphy, meaning “beautiful writing”, was first used in 1590, calligrapher was not a word used in Esther Inglis’ lifetime. Early-modern writing masters competed against each other to prove their skills in handwriting, publishing manuals to demonstrate the range of their abilities and advertise themselves as teachers. Click the arrows to learn more about handwriting in this period.

|

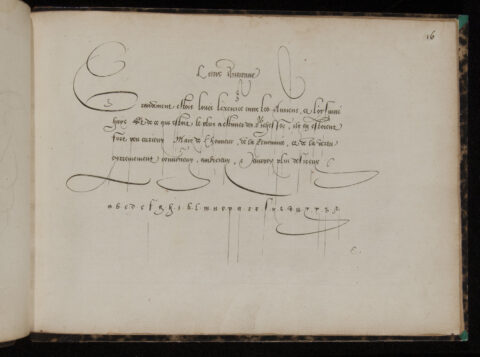

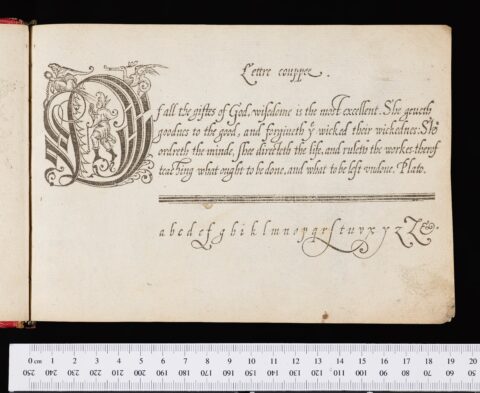

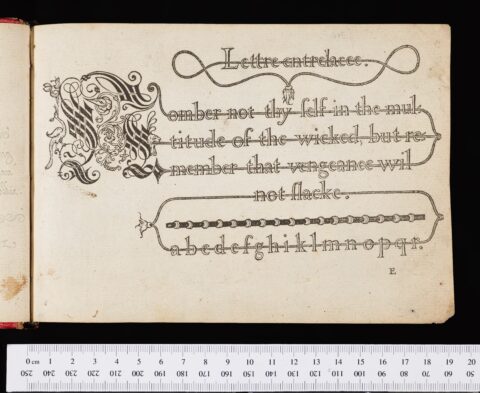

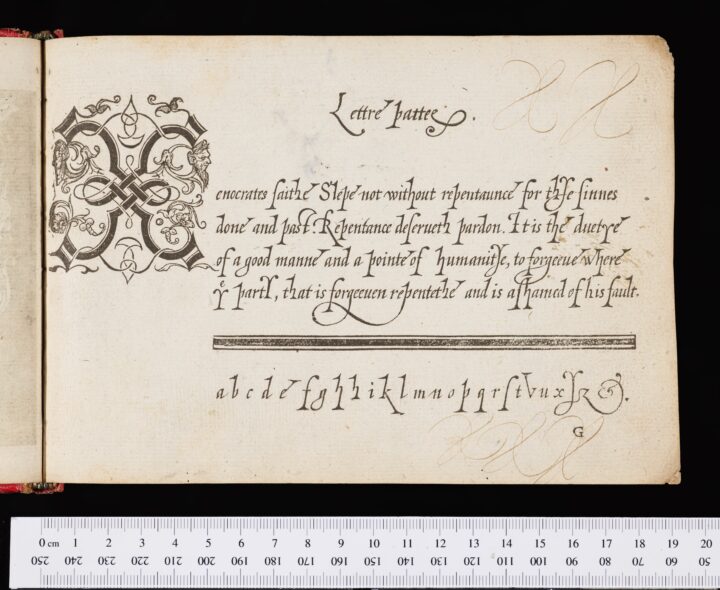

Writing manuals could be printed as well as hand-written, and this meant that French, Italian or English manuals were also available to pupils in Scotland. In Edinburgh, Esther Inglis was most influenced by French writing manuals, and many of the scripts she used were copied from other Huguenot writing masters, including those in London. Click the images to discover some of the scripts Esther Inglis learnt from these sources.

Fragments from an Edinburgh writing-master

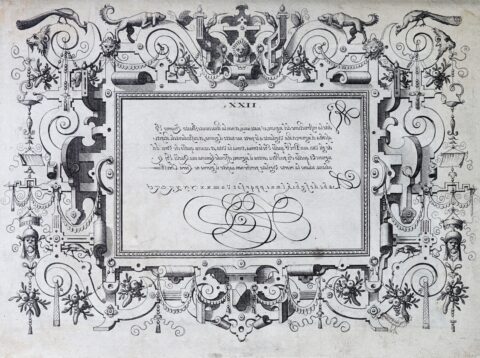

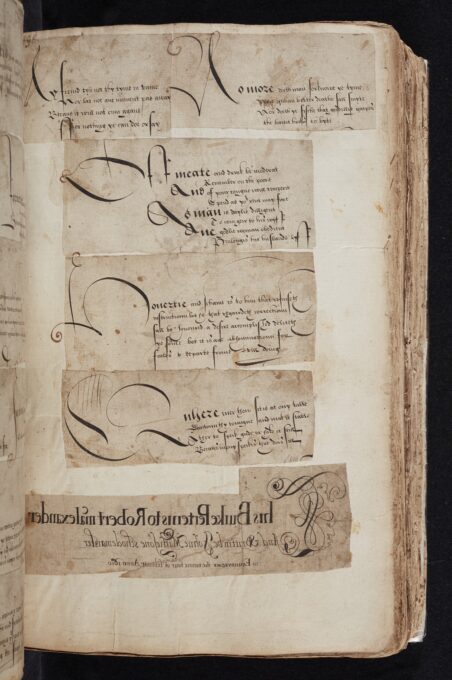

When producing their handwriting manuals, early-modern writing masters were careful to show the superiority of their skills compared to those of their pupils. These fragments are taken from a handwriting manual produced in 1610 by John Mathesone, a schoolmaster in Edinburgh and a contemporary of Esther Inglis. The examples which Mathesone writes for his pupils to copy are all in secretary hand, but in signing his manual he also demonstrates that he can work in italic, roman, gothic, and reversed scripts.

|

|

This manuscript is Esther Inglis’ own interpretation of an early modern handwriting manual and is likely to have been produced early in her life. It shows the different scripts she had learned, studying with her mother’s guidance and copying from printed writing-manuals. Here, Inglis uses a range of early-modern scripts to copy out quotations from the Book of Proverbs. In 1605, she added a dedication to this writing-manual, offering these beautifully written Proverbs as a gift to the Lady Susan Herbert. In this way, Inglis transformed her early writing-book into a calligraphic devotional manuscript.

View the full manuscript here.

|

||||||

| Object reference | Houghton Library, MS Typ 428.1, folio 30r | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit / Usage information | Houghton Library, Harvard University |

Moves into the miniature

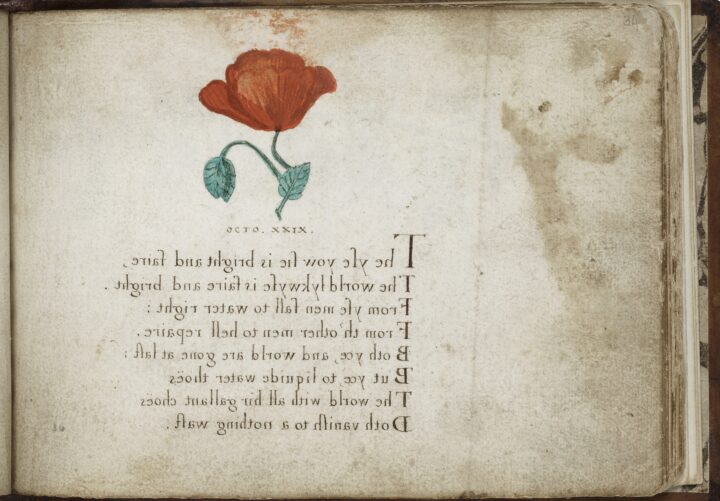

Some early-modern scribes experimented with miniature writing, but only a few produced miniature books. Esther Inglis developed an early interest in miniaturisation, making several tiny books which contained the same range of scripts as her larger volumes. These books sit within the palm of the hand, drawing a viewer’s full attention towards the scripts and religious words within their pages. Their small size only adds to their all-absorbing curiosity; each page measures just 7 by 5 centimetres.

Click here to discover another of Esther Inglis’ miniature manuscripts from 1599, now in the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

|

An ever-changing repertoire

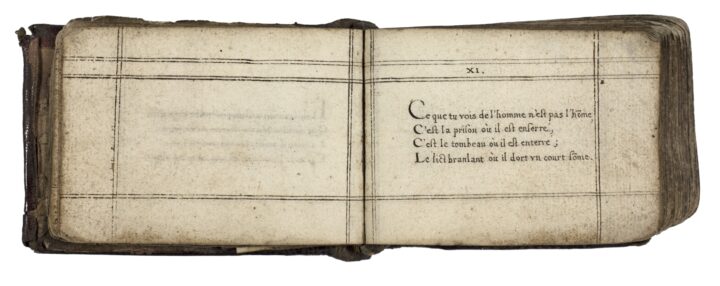

Esther Inglis’ use of script developed throughout her career, and was constantly changing. In the colourful manuscripts which she made between 1600 and 1607, she added further scripts to her already extensive repertoire -- including mirror writing. Later in her career, Esther Inglis would instead turn her attention more closely towards scripts which imitated a printed text.

Click here to view this manuscript in full.

|

Esther Inglis was just one of many scribes who produced manuscripts as gifts in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The practice of gift-giving was well-established in Europe and was used for many different purposes. These manuscripts were all made for presentation in late-sixteenth-century Scotland, and include deliberately high-grade scripts and decoration. In their quality, variety, and precision, however, it is clear that Esther Inglis’ manuscripts still outshine these examples. Click the images below to learn more.

Having first learned calligraphy from her mother, Esther Inglis continued a female line of handwriting which rivalled the work of other male professional writers. In Esther Inglis’ Protestant society, the copying and learning of letters was considered appropriate for women because it was passive activity. But Esther Inglis’ calligraphy is an active force: disrupting social norms and expressing her autonomy, education, and creativity as a woman. Read on to discover how and why Esther Inglis presented her manuscripts to the recipients she chose.