In her own work, Esther Inglis combines the early-modern art of limned portraits with older illumination traditions. Read on to discover how Esther Inglis develops the medieval practice of limning in her seventeenth-century manuscripts.

The Art of Limning

Esther Inglis described herself as both “writing” and “limning” her manuscripts. The word “limner” dates from the fourteenth century and first referred to someone who decorated manuscripts with gold and colours. However, the demand for limning was significantly affected by the waves of religious reform which affected England and Scotland in the middle of the sixteenth century. Books produced in these countries after their reformations were generally less lavishly decorated than before. The medieval tradition of limning instead evolved into the painting of miniature portraits, which remained popular well into the seventeenth century.

Esther Inglis’ work presents her as a “limner” in the fullest sense; she is influenced by illuminated medieval manuscripts, but also draws on contemporary sources and adapts the style of a Renaissance portrait miniaturist. Her manuscripts develop artistic traditions which were more than a century old, while also intentionally modernising them.

|

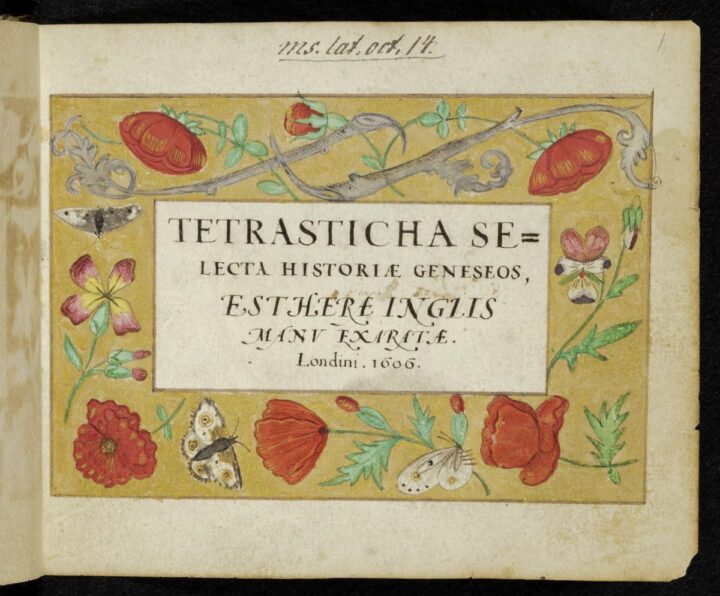

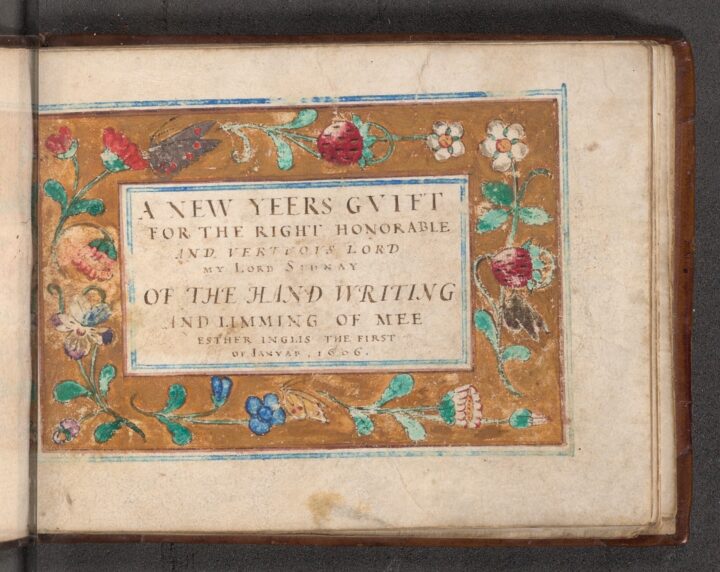

“the hand writing and limming of mee Esther Inglis”

Esther Inglis describes this illuminated manuscript as containing both her “hand writing” and her “limming”. The manuscript was made as a gift for Robert Sidney, 1st Earl of Leicester, and unlike most of Inglis’ works it was produced on parchment rather than paper. Of the 63 manuscripts by Esther Inglis which are known today, more than 20 have oblong formats and illuminated title-pages like this one. Her illuminated manuscripts are all devotional in nature, with many containing Biblical summaries, quotations, or spiritual verse composed by sixteenth-century poets.

Click here to see a full digitisation of this manuscript.

|

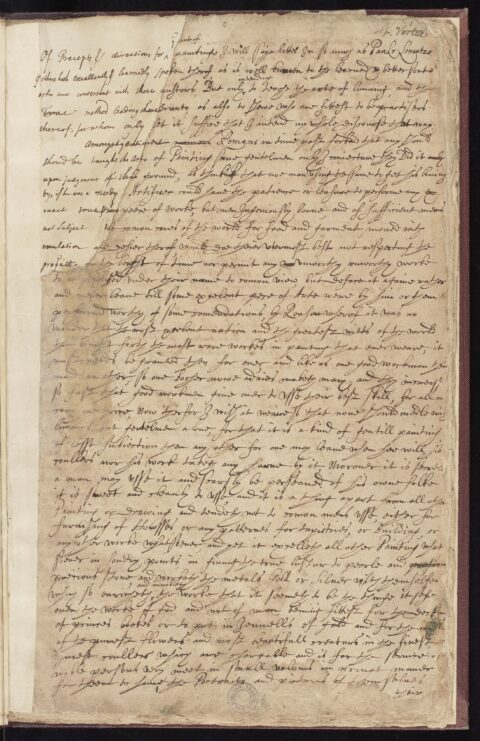

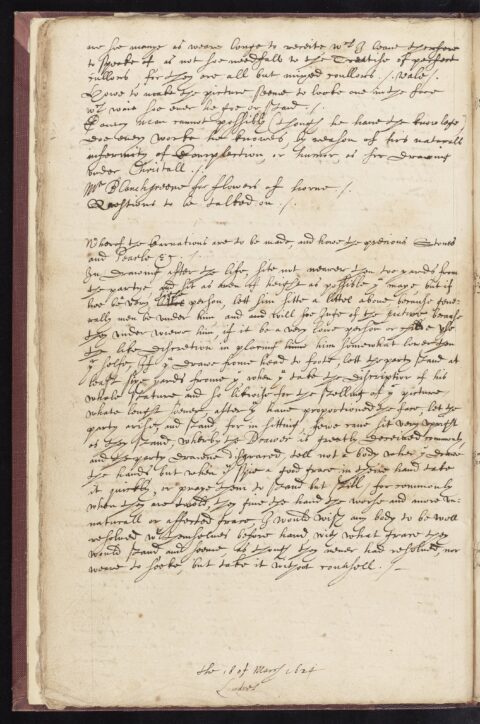

A Treatise on the Art of Limning

Nicholas Hilliard’s Treatise concerning the Art of Limning (c. 1600) sets out the tools and techniques required for limning, in all its forms, at the end of the sixteenth century. In his introduction to the art, shown in the first extract below, Hilliard defines limning as “the decking of princes bookes” and “the imitation of the purest flowers”, but much of this Treatise also focuses on the painting of miniature portraits. In the second extract, Hilliard explains how close the artist should sit to their subject when painting their portrait, and which positions would be most flattering for their sitter. Click the images below to learn more.

Limning through time

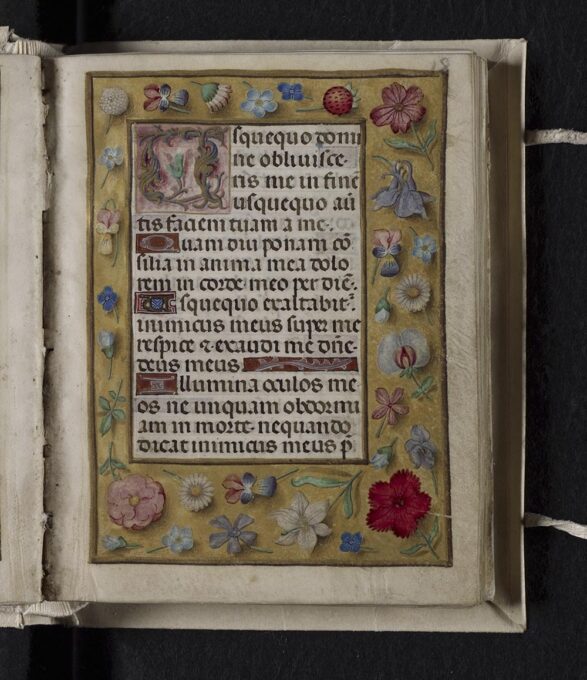

The coloured manuscripts which Esther Inglis produced between 1600 and 1608 adapt and respond to the style of illumination found in Flemish manuscripts from the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. This style, known as “Ghent-Bruges” after the regions in which it developed, includes realistic flowers, animals, and fruit painted against a golden or yellow ground. This illuminated manuscript was produced in the Netherlands for export to Scotland; it was made for James Brown, Dean of Aberdeen.

|

Esther Inglis painted botanical images throughout the pages of her illuminated manuscripts, so that each spiritual verse or text would be accompanied by a different flower, fruit, or creature. These individual images of nature could become focal points for a viewer’s contemplation, thinking of a single flower as a symbol of divine creation. With every turn of the page, Esther Inglis offers her audiences a choice between focussing on the words of a devotional text or an element of the natural world, believing that each could guide the viewer towards the divine.

Click here to see a full digitisation of this manuscript.

|

||||||

| Object reference | Edinburgh University Library, MS La.III.439, folios 21v-22r | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit / Usage information | University of Edinburgh |

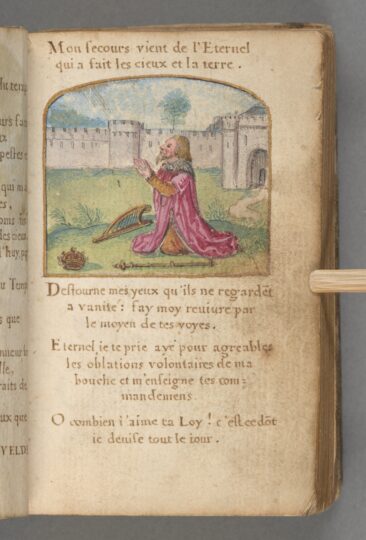

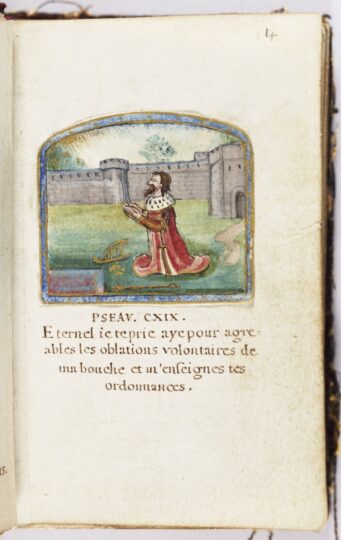

Esther Inglis’ limning also extended to the painting of miniature scenes, such as would be found in medieval illuminated manuscripts. Between 1612 and 1615, she made several small Books of Psalms which open with miniature paintings of King David, traditionally identified as the author of many of the Psalms. Again, it is likely that Esther Inglis was familiar with the paintings found in Flemish illuminated manuscripts from the late-fifteenth and early-sixteenth centuries. Click the images below to see her paintings in more detail.

|

|

|

This image of King David is taken from a Book of Hours produced in the Netherlands around the year 1500. Many of its illuminations are the work of Gerard Horenbout, who lived and worked in Ghent and was one of the greatest limners of his time. Many illuminated Books of Hours produced in the Netherlands around this time were exported for English or Scottish owners, and Esther Inglis must have had access to such a manuscript herself. The miniature images of King David which she painted for her own Books of Psalms also include the red robe, gold sleeves, kneeled position and architectural background found in Gerard Horenbout’s illumination.

|

As a seventeenth-century limner, Esther Inglis also mastered the painting of miniature portraits, following the work of Renaissance artists like Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619) and Isaac Oliver (c.1565-1617). Learn more about this in the next section which introduces Esther Inglis’ self-portraiture.