But Esther Inglis’ artistry extends even further than her penwork drawings and intricate needlework. Read on to learn more about Esther Inglis’ as an illuminator or limner of manuscripts.

Pen and needlework

In 1599, the writer and theologian Robert Rollock wrote of Inglis’ work that “with the pen, the needle strives”. Esther Inglis’ manuscripts contain much more just her handwriting — they also include detailed penwork drawings, four different types of artistic self-portrait, and hand-painted miniatures, while many are also covered in her own needlework. At a time when the writing, decorating, and binding of books would usually have each been done by different individuals, Esther Inglis was responsible for nearly every element of her manuscripts’ creation. Read on to find out more.

From print to manuscript

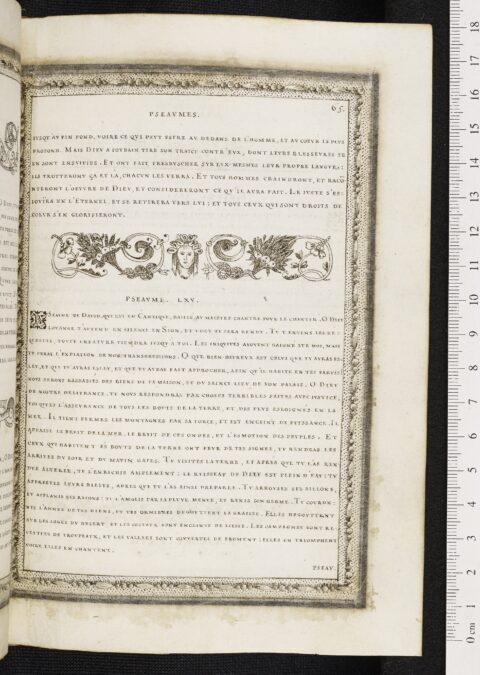

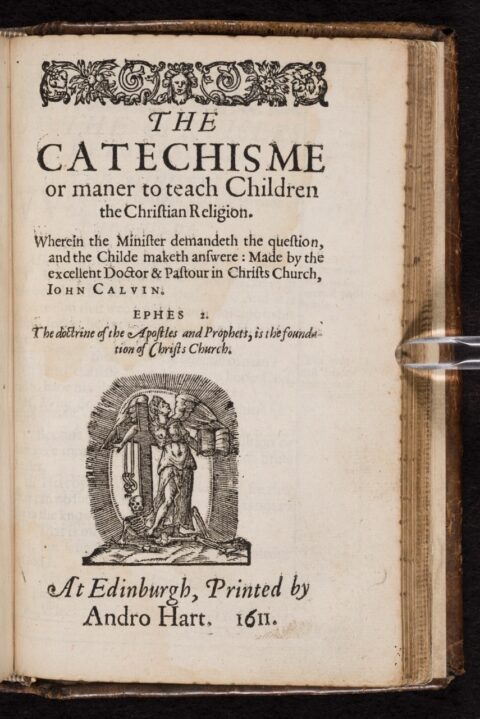

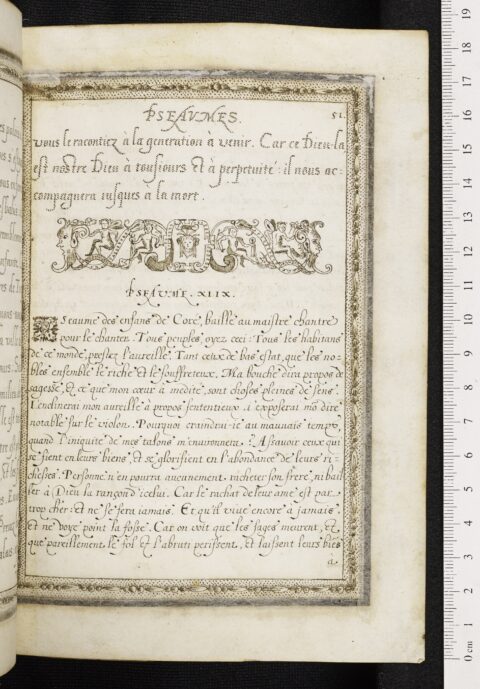

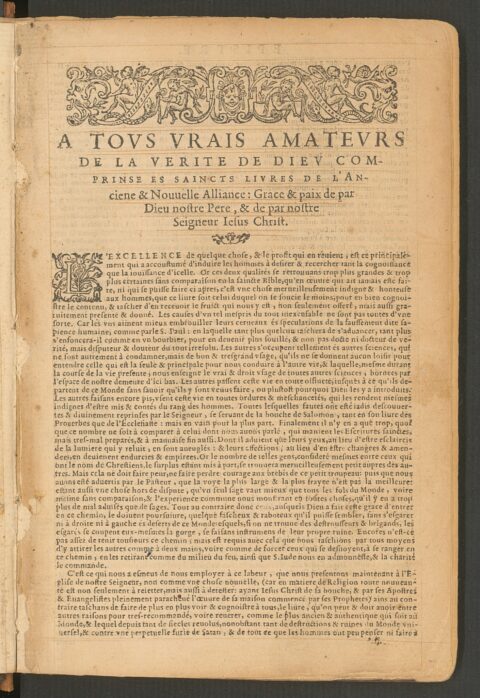

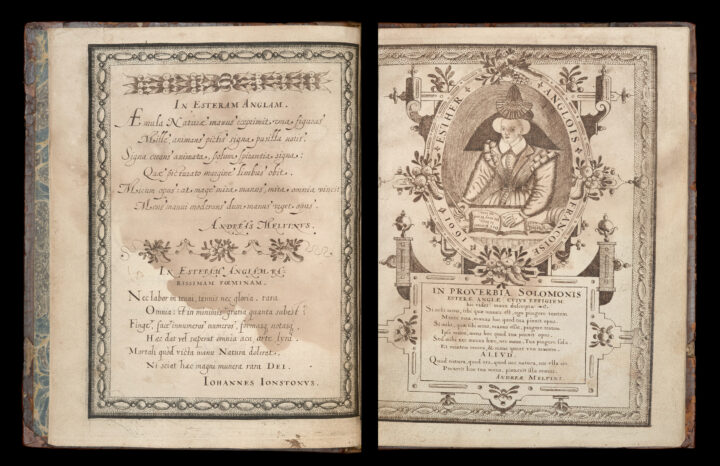

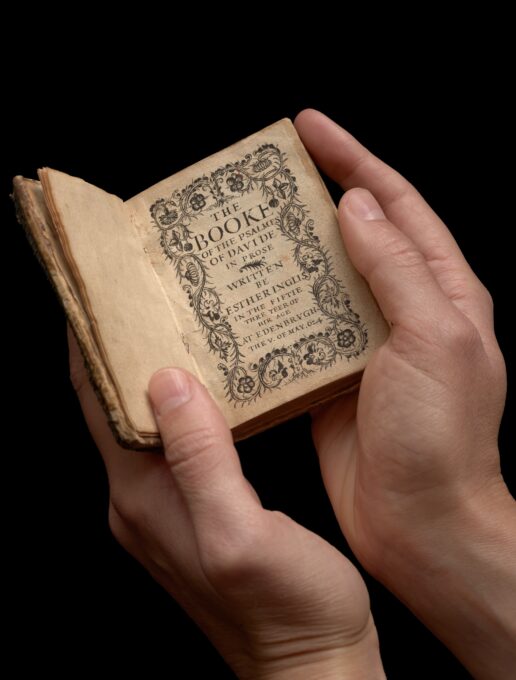

Many of Esther Inglis’ manuscripts are written and drawn to look like printed books. By imitating print with such exceptional precision, Esther Inglis could show her true mastery of handwriting. Against the spread of printed books and the printing press at the end of the sixteenth century, Esther Inglis shows her audiences that there is nothing the press can do which cannot also be done by hand. Click the images below to see some of the designs she copies from printed books.

Spot the difference?

Many features of Esther Inglis’ monochrome manuscripts trick their viewers into thinking they are printed – but the borders of this book of Proverbs really are printed engravings. On the page containing her self-portrait, Esther Inglis copies this printed border by hand; at first glance the borders look identical, but close inspection reveals their difference. These tricks which Esther Inglis plays on her audiences show the depth of her skills as a writer and an artist.

|

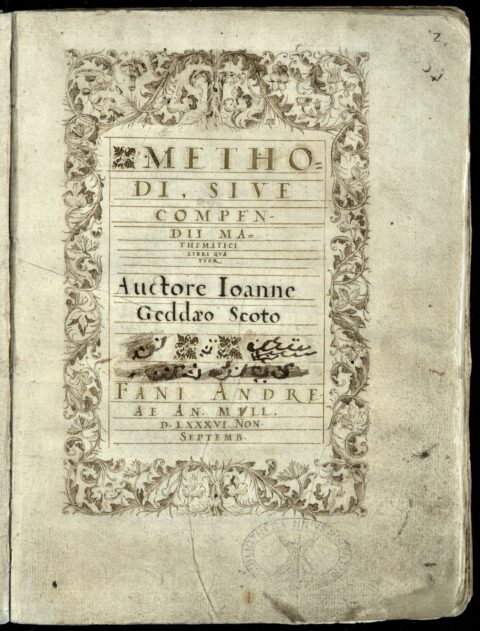

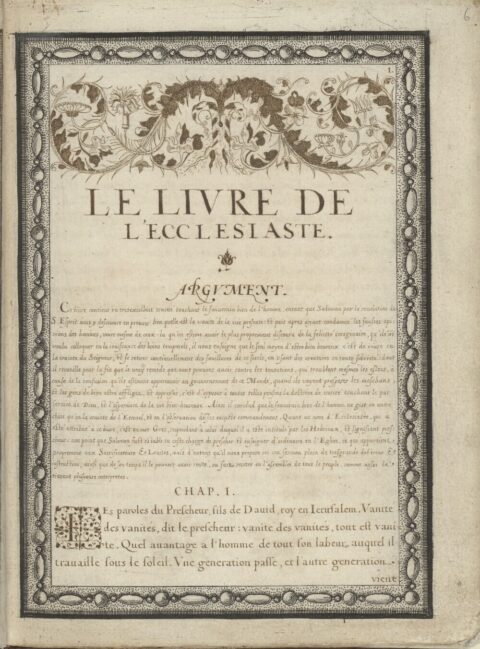

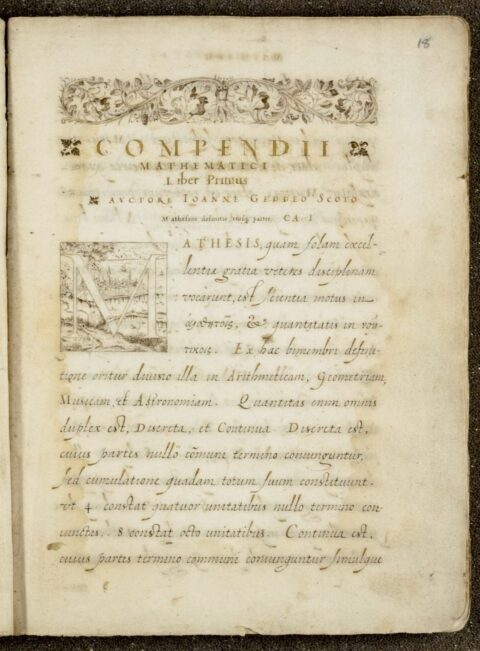

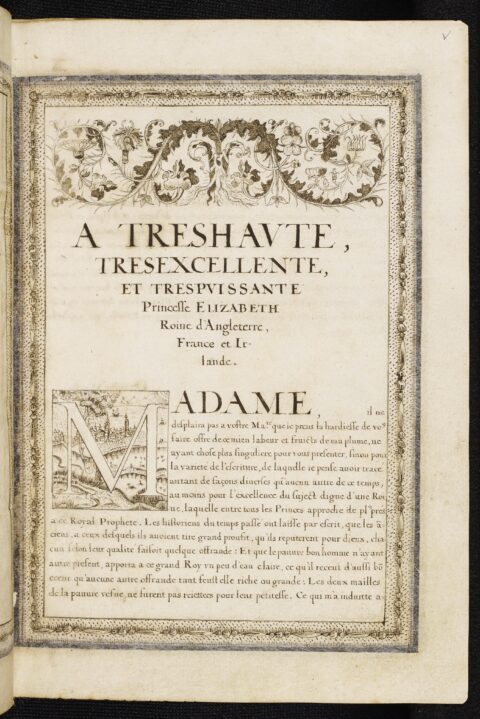

As a skilled draughtswoman working with the pen, Esther Inglis also copied the hand-drawn decoration of other scribes or artists. A manuscript made by the royal scribe John Geddy in 1586, as a gift for King James VI, contains delicate pen-work designs in its borders and its decorative and historiated initials. Esther Inglis reworked these designs in many of the manuscripts she made between 1599 and 1602, either copying them directly or adapting elements of Geddy’s penwork. Esther Inglis incorporates the decorative initials in Geddy’s manuscript into her own work, and copies the design of twisted foliage from its title-page. This important link between John Geddy and Esther Inglis suggests that she was part of a wider scribal network in Edinburgh – and perhaps also St Andrews, where Geddy's manuscript was written in 1586.

Click the images below to see close-up comparisons of the pen-work drawings by John Geddy and Esther Inglis.

The connection between Geddy’s work and Esther Inglis’ calligraphy continued until the very end of her career. In 1624, Inglis reused the design of a tree surrounded with swirling vines which was originally found in Geddy’s manuscript of 1586. The later use of this design also brings Esther Inglis’ oeuvre full-circle; the decoration in the last manuscripts she ever produced is also a reference to the early manuscripts she made between 1599 and 1602.

|

With the pen the needle strives

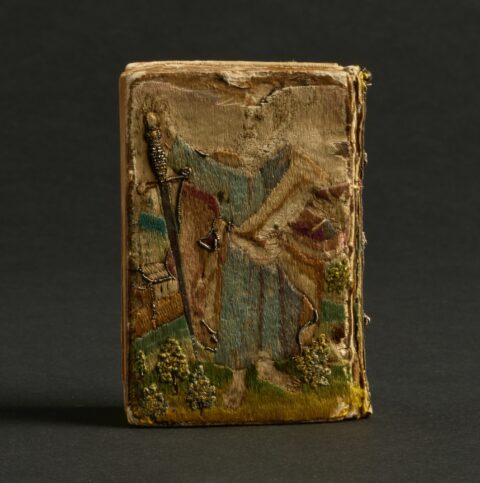

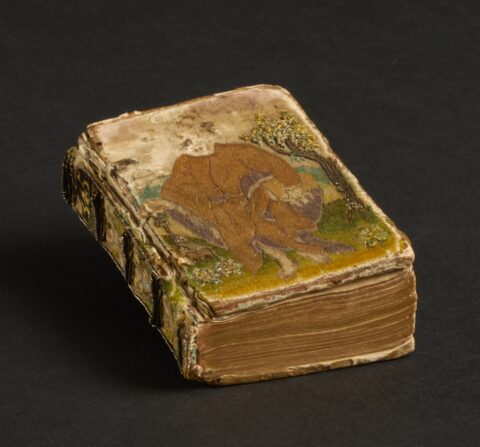

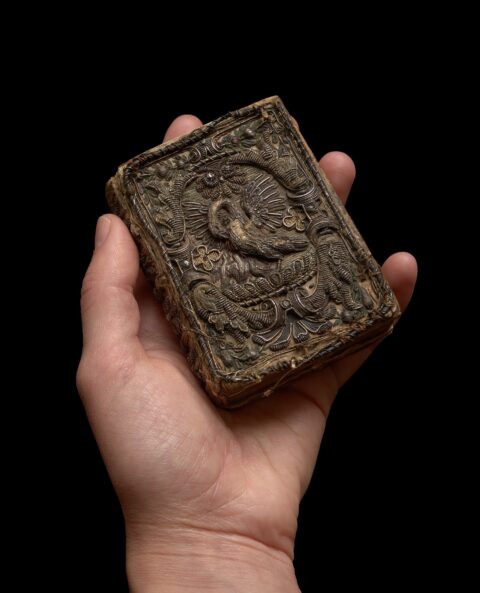

Although most of her books are bound in leather, fifteen of Esther Inglis’ surviving manuscripts have intricate embroidered bindings. Some of this embroidery was Inglis’ own work; as well as a scribe and artist, she can also be known today as a needleworker. Esther Inglis knew that the covers of her manuscripts would also carry meaning for their recipients, and their designs are often symbolic. Click the images below to see close-up examples of the embroidered bindings on Esther Inglis’ manuscripts.

|

Esther Inglis designed this manuscript with a ‘dos-a-dos' (shoulder to shoulder) binding; it is made in two halves and can be read from either the front or back. It contains a copy of the English poet John Taylor’s printed verse summaries of all the books of the Bible. Esther produced it as a gift for her eldest son, Samuel, in 1615. Although many details of the original needlework have now worn away, this cover probably depicted Moses with the tablets of the Ten Commandments, the principles on which the Christian faith is built.

This is Esther Inglis’ smallest known manuscript; its pages are just 5 centimetres tall.

Read more about Samuel Kello here and view the full manuscript here.

|

||||||

| Object reference | Houghton Library, Harvard, MS Typ 49, upper board | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Credit / Usage information | Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. |